INTRODUCTION

The Paris range of the internationally successful Irish lighting company, Mullan (founded 2008), is a reminder of how French culture continues to influence Irish designers. Indeed, deep connections between Ireland and France stretch back centuries. From the establishment of the Irish College in Paris in 1578 to the championing of James Joyce’s Ulysses by the Paris-based, publisher Sylvia Beach in 1922, Irish people have long benefitted from French cultural life. But what might be less well known is the huge impact generations of Irish designers have made in France. Design historian Dr. Linda King focuses on some key examples of this relationship.

EILEEN GRAY

ARCHITECT & DESIGNER

Eileen Gray (1878-1976) was born in Enniscorthy, County Wexford and became one of the most influential designers of the 20th century. A pioneer of furniture, architecture and lacquer-work for small apartments and houses, she also had a gift for graphic and textile design proclaiming that ‘To create, one must first question everything’.

The Salon at the Boulevard Suchet apartment as shown in L’illustration (1933) and featuring the Dragon and Bibendum chairs © National Museum of Ireland

The Salon at the Boulevard Suchet apartment as shown in L’illustration (1933) and featuring the Dragon and Bibendum chairs © National Museum of Ireland

Gray moved to London in 1900 where her independent wealth enabled her to study painting at the Slade School of Fine Art. She relocated to Paris in 1906 to study lacquer-work, leading to several high-profile furniture and interior design commissions from wealthy Parisians. Work from this period includes the Dragon or Serpent Chair (1919), which gained notoriety when it sold for almost €22 million as part Yves St Laurent’s estate in 2009.

‘TO CREATE, ONE MUST FIRST QUESTION EVERYTHING'.

Once settled permanently in France, her work became bolder and simpler in shape. Her Brick Screen (1922) was made of rectangular panels that pivot to deflect light, while her bulbous Bibendum Chair (1930) in leather and chromed metal, referenced the Michelin Man or ‘brand character’ of the Michelin Tyre Company.

White Block Screen © National Museum of Ireland

White Block Screen © National Museum of Ireland

Shop front of Jean Désert © National Museum of Ireland

Shop front of Jean Désert © National Museum of Ireland

Gray opened her own store in 1922, the Galerie Jean Désert on rue Du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. There she sold her furniture and carpets, deliberately using a masculine-sounding name to disguise her gender. The crème of Parisian society flocked to the store. Joyce, Beach, Ezra Pound, Elsa Schiaparelli and Loie Fuller were amongst her many clients, while Irish artists Evie Hone and Mainie Jellett were amongst her friends.

Gray became interested in architecture; she was self-taught, eagerly following and connecting with the most avant-garde European architects of the time. Her most radical work was created for her own homes. With these projects she explored modern ideas of space, form and materials.

Her most significant architectural project, E-1027 (1929), was the holiday home she designed for herself and her lover Jean Badovici, the Romanian architect and critic. The industrial sounding name of the house references the initials of their names (E for ‘Eileen’, 10 for ‘J’, the 10th letter in the English alphabet representing ‘Jean’, etc.) to acknowledge their personal and professional collaborations.

The building’s design reflects its maritime location at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in the South of France: it looks almost like an ocean liner, docked at the water’s edge. Raised up on columns, with white walls and ribbon windows, it was influenced by the work of French-Swiss architect le Corbusier. He became obsessed with and jealous of Gray’s work and defaced the building with a series of murals after she moved out in 1931.

Bibendum chair, 1930. Chrome-plated steel tubing and canvas upholstery.

Transat (short for transatlantic) chair, 1926. Chrome tubular steel and leather upholstery

Maritime map with collage "Invitation au voyage" (invitation to travel) a reference to the Baudelaire poem and "Beau Temps" (good weather).

Centimetre Rug, 1926. Hand-knotted wool. The number 10 represents the tenth letter of the alphabet: J for Jean Badovici.

Living room at E-1027, featuring the Bibendum and Transat chairs © National Museum of Ireland

There is a humanity and practicality in E-1027 that pre-empts our contemporary expectations of a well designed, modern home. The open-plan design follows the movement of the sun for maximum light, the indoor spaces and outdoor spaces merge into each other, storage is plentiful and cleverly concealed, tables are covered in cork to minimize the noise of crockery and utensils, and shaving mirrors can be angled and positioned for maximum visibility.

THERE IS A HUMANITY AND PRACTICALITY IN E-1027 THAT PRE-EMPTS OUR CONTEMPORARY EXPECTATIONS OF A WELL DESIGNED, MODERN HOME.

Two items exemplify this emphasis on functionality and practicality: a glass and chrome-plated side table can be adjusted to various heights, while the Transat Chair, based on a ship’s deck chair, is designed for comfort. Another embodies her individualism: the Non-Conformist Chair (1929) has only one armrest.

Adustable table © National Museum of Ireland

Adustable table © National Museum of Ireland

Gray was both of and ahead of her time. In response to France’s post-WW1 housing shortage she designed the Ellipse House (1936), a prototype for a small, pre-fabricated, dwelling that was never realised. Unfortunately, from the 1930s onwards, Gray drifted into obscurity until a number of exhibitions in Britain and the U.S. renewed interest in her work.

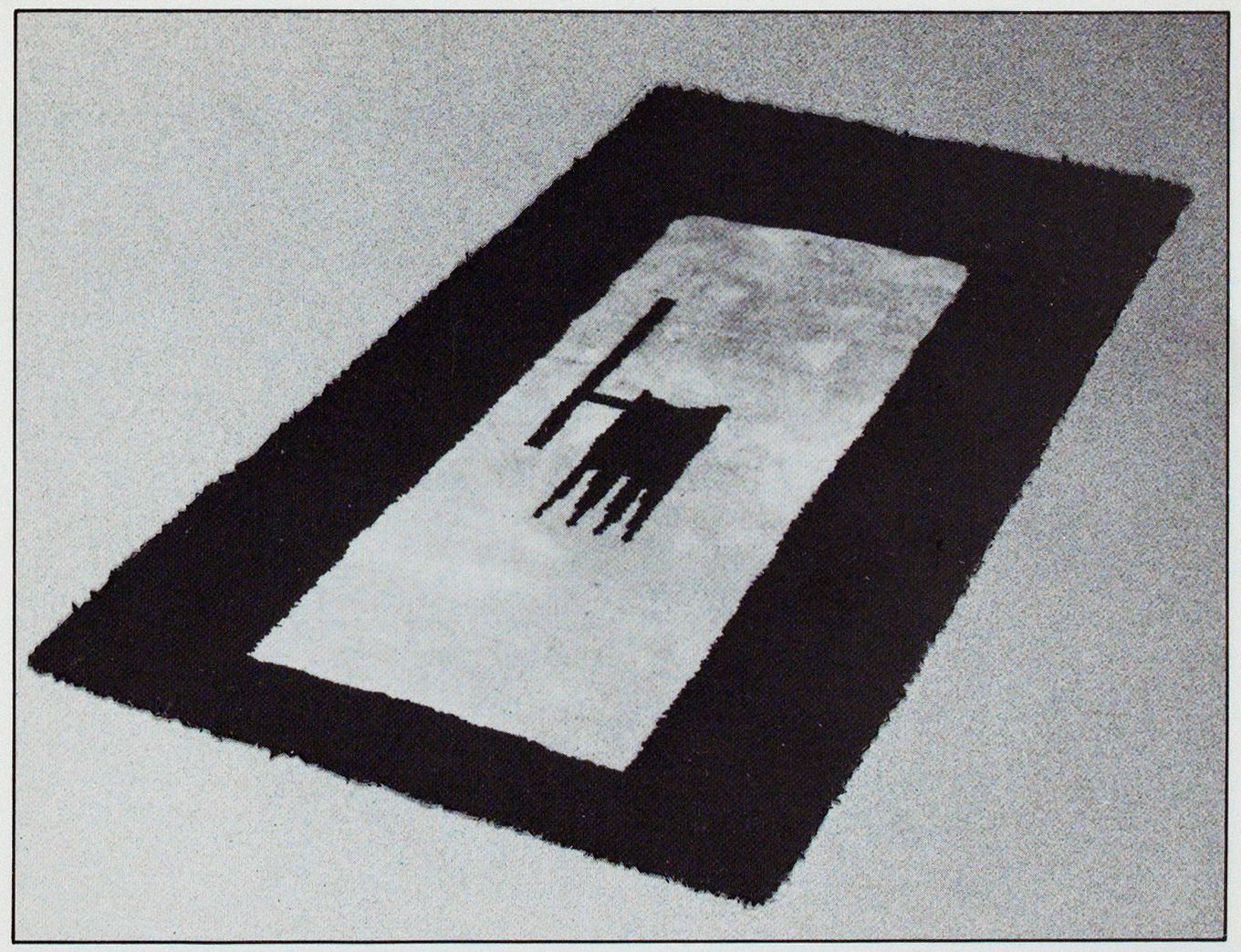

Although Gray never returned to live in Ireland, her Irish roots remained important to her. Jean Désert sold rugs called Kilkenny, Wexford, Irlande and Ulysses, while the guest bedroom in E-1027 had a rug called Irish Green. One of Gray’s last wishes were that some of these might be manufactured in Ireland. In 1975, Donegal Carpets manufactured Wexford and Kilkenny, a year before she died aged 98.

Eileen Gray Carpets booklet © National Museum of Ireland

Eileen Gray Carpets booklet © National Museum of Ireland

Wexford 1.80x1.00m Black ground, beige design / © National Museum of Ireland

Wexford 1.80x1.00m Black ground, beige design / © National Museum of Ireland

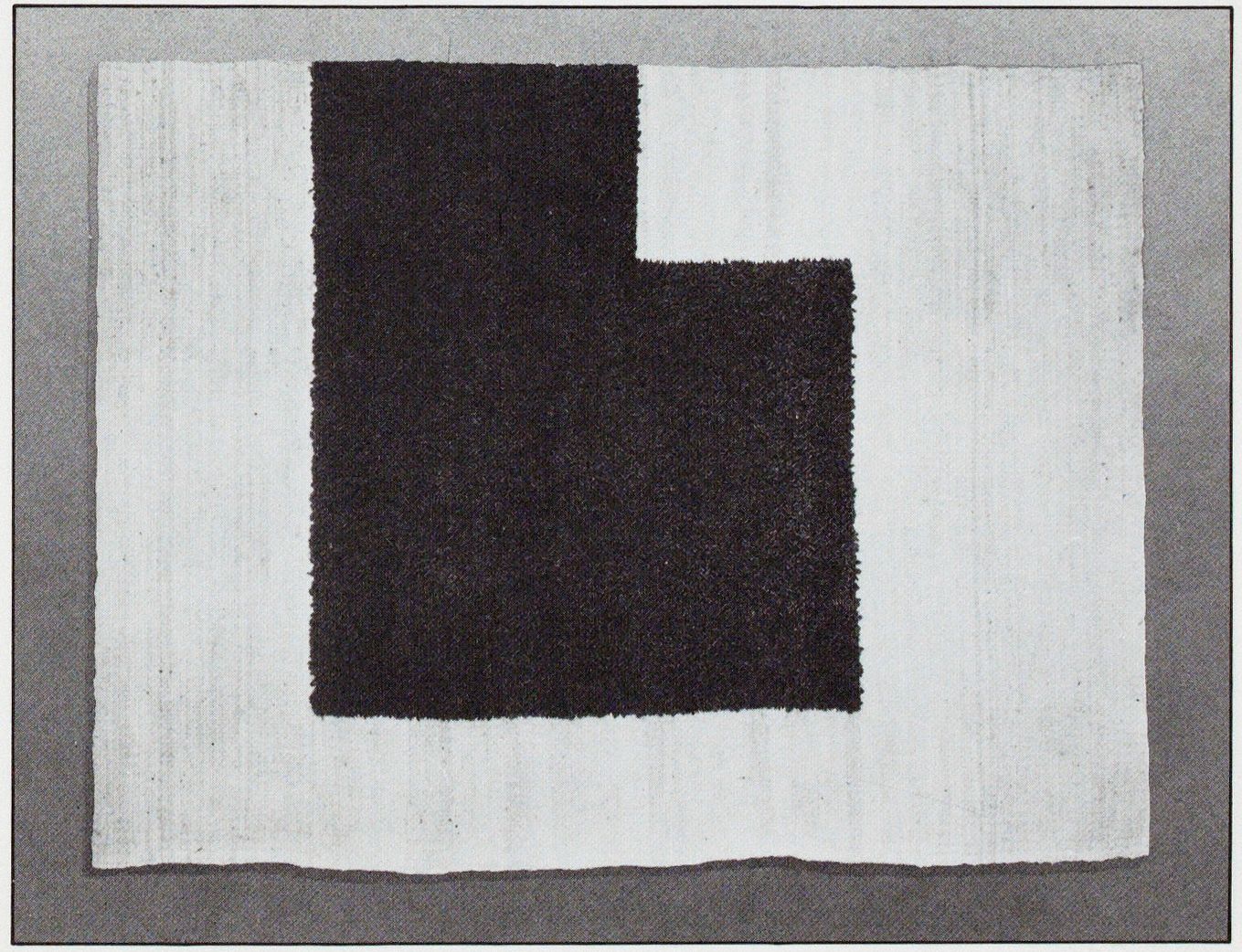

Kilkenny 1.68x1.44m Off-white ground, mid green design / © National Museum of Ireland

Kilkenny 1.68x1.44m Off-white ground, mid green design / © National Museum of Ireland

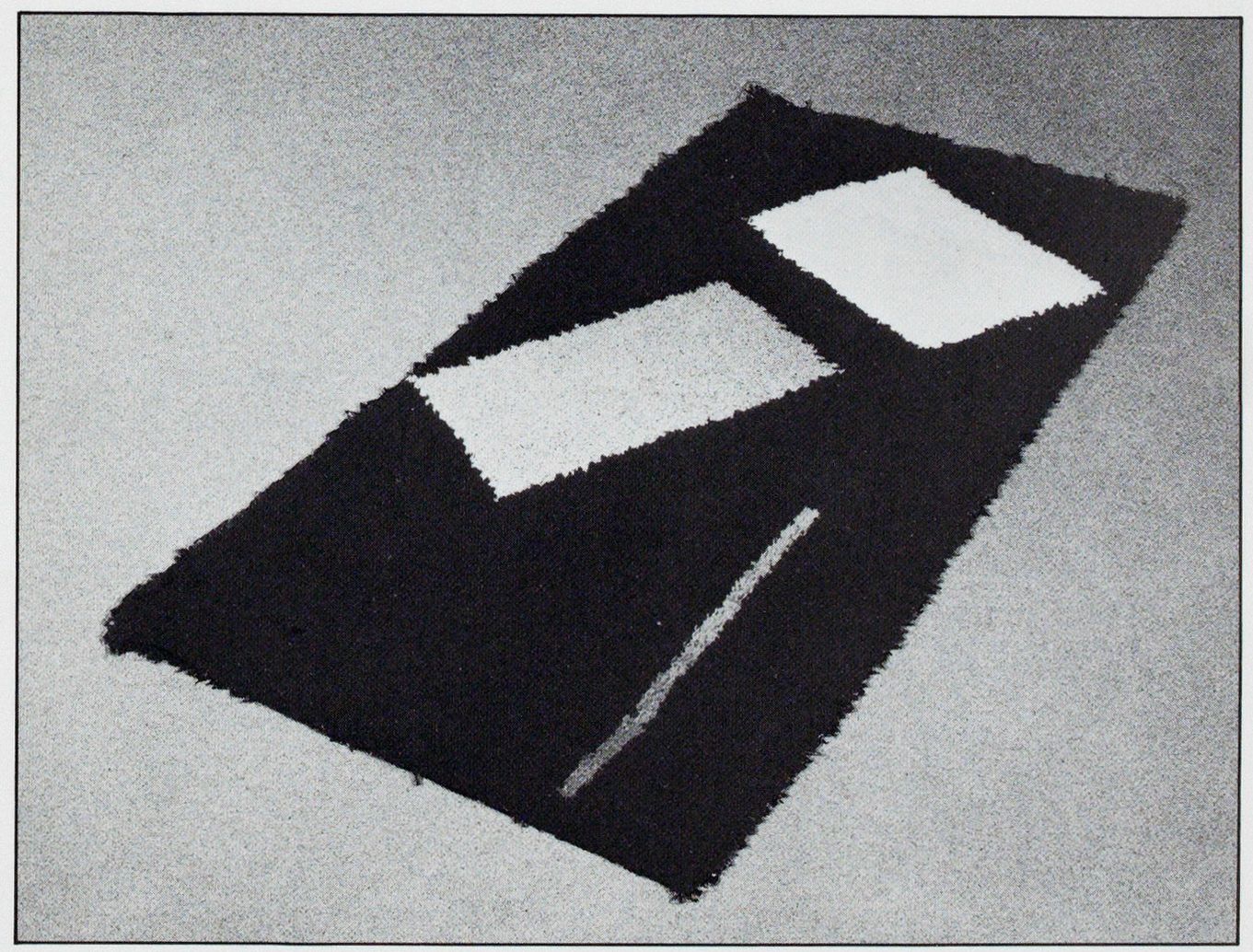

Bonaparte 2.10 x 1.00m Black ground, off-white and bisquit rectangles with pink stripe / © National Museum of Ireland

Bonaparte 2.10 x 1.00m Black ground, off-white and bisquit rectangles with pink stripe / © National Museum of Ireland

In 1997 the National Museum of Ireland opened a permanent exhibition of her work, while in 2013 the Pompidou Centre, Paris and the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, co-curated the largest retrospective of her work to date. In 2021 E-1027 opened to the public after many years of restoration.

PETER RICE

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER

In 2019, the Irish Examiner described Peter Rice (1935-92) as ‘the brilliant, gifted and world-class Irish engineer you may never have heard of’. While his name may not be well known outside of design circles, he worked on some of the most famous and structurally ambitious buildings in the world, collaborating with visionary architects. Such works include the Sydney Opera House (1973) with Jørn Utzon, the football stadium Stadio San Nicola in Bari (1990) with Renzo Piano, Standsted Airport in Essex (1991) with Norman Foster, and several buildings in France including the Pompidou Centre in Paris (1977) with Piano, Richard Rogers, Su Rogers and Gianfranco Franchini.

'THE BRILLIANT, GIFTED AND WORLD-CLASS IRISH ENGINEER YOU MAY NEVER HAVE HEARD OF'.

Sydney Opera House

Sydney Opera House

Rice grew up in Dundalk, County Louth. He studied at Queen’s University, Belfast and Imperial College, London, moving from aeronautical to civil engineering. His professional career began in 1956 with the world-famous engineering company Ove Arup. His first job was working on the roof of the Sydney Opera House, helping to solve the mechanics of how to hold up a concrete roof structure that Utzon had based on the shape of orange segments.

Le Centre Pompidou

Le Centre Pompidou

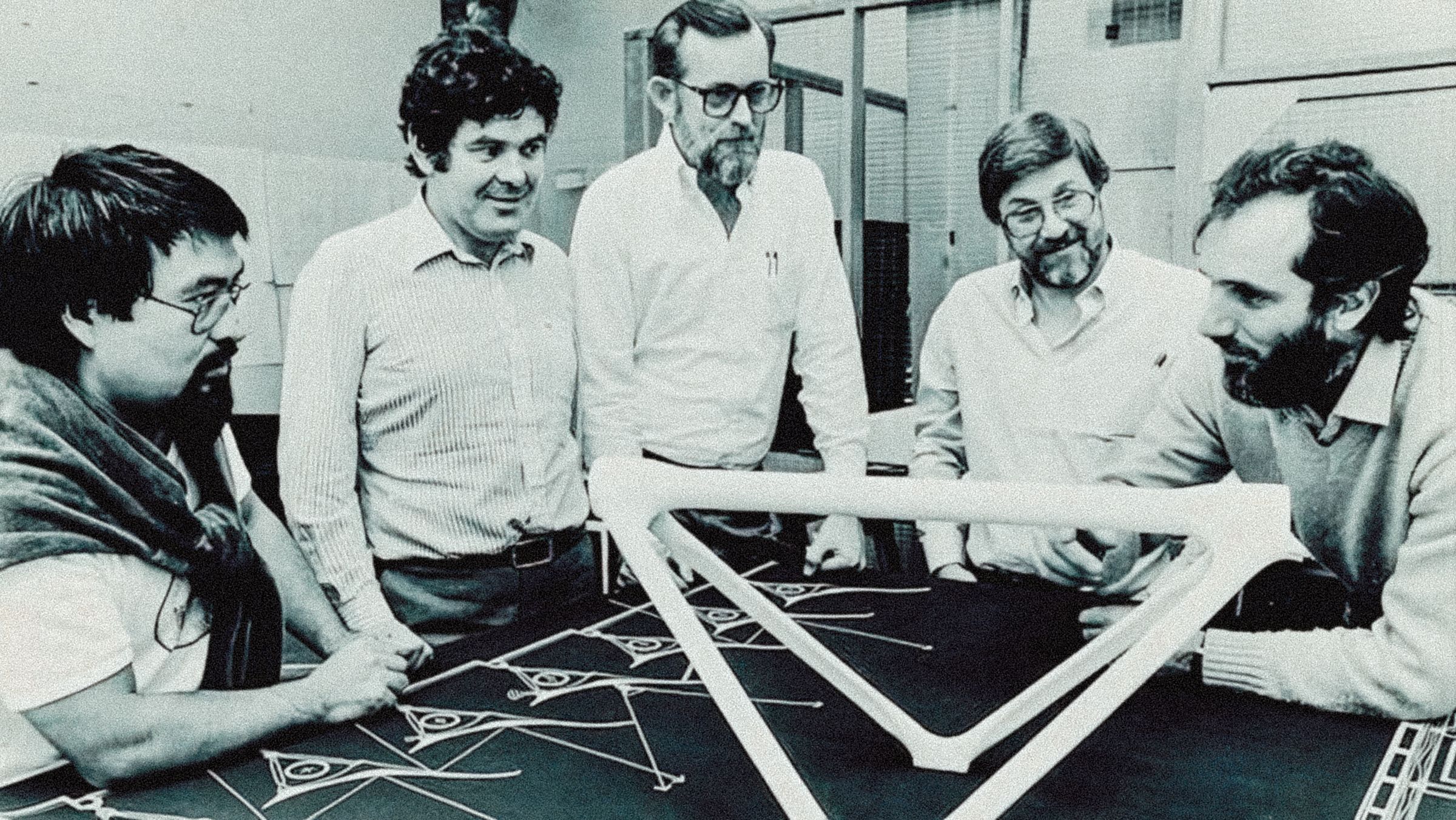

With a growing reputation for technological innovation and exploiting the qualities of materials, Rice became the principal engineer for the Pompidou in 1971, a new arts center and public library in Beaubourg, Paris. The building was deliberately provocative, challenging perceptions of what a museum should look like. The structural and mechanical elements that are typically disguised within the skeleton of a building were placed on its exterior and colour-coded, thus green plumbing pipes, yellow electrical wires, blue climate control ducts and red safety devices are clearly visible. His colleagues credited him with being the ‘gel’ that brought and kept a diverse team of individuals together, enabling them to realise this complex vision.

'THE JAMES JOYCE OF STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING'

The Pompidou exemplified Rice’s philosophy of working on projects that benefitted society. He fell in love with Paris while working on this building and after its completion in 1977, he established a cross-disciplinary design practice in Paris the same year. Called RFR, his partners were industrial designer Martin Francis and architect Ian Ritchie (who designed Dublin’s Spire in 2004). He worked on many more projects in France, excelling in glass technology. One of his inventions was the cable-stay system that holds the glazing of the Louvre Pyramid (1988) in place, a project he collaborated on with the architect IM Pei.

La Défense, Paris

La Défense, Paris

Other French-based work includes TGV stations for the SNCF, various projects for the purpose-built business district of La Défense, and a new façade for the Cathedral Notre Dame de la Treille in Lille, completed posthumously. One of his most ‘poetic’ projects was also one of his last: in 1992 he created an outdoor theatre space for the Full Moon Theatre Company, in Gourgoubès, where the stage and performers were solely lit by reflected moon light.

Just before he died, aged 57, Rice was awarded the Gold Medal for Architecture by the Royal Institute of British Architects, a highly unusual accolade for an engineer but a testament to the breadth of his talent. His obituary in The Independent (London) referred to him as the ‘James Joyce of structural engineering’, referencing his ‘poetic invention’ and ‘rigorous mathematical and philosophical logic’. In 2013 the Farmleigh Gallery, Phoenix Park, Dublin hosted the exhibition Traces of Peter Rice. His innovative glass technology system can be found in many Irish buildings including the CHQ Building in Dublin’s IFSC.

PETER O'BRIEN

FASHION DESIGNER

As the world’s fashion capital, most designers can only dream of working in Paris; even less can hope to work for one of the big fashion houses, let alone become its Creative Director. Yet Dubliner Peter O’Brien worked for Dior, Givenchy, Chloe and Rochas, and is, as the Irish Times noted in 2017, ‘the only Irish fashion designer to have carved a successful career in haute couture in Paris’. O’Brien has stated ‘I’m not crazy about fashion but I love clothes’. Yet, his designs graced the catwalks of Paris for 22 years, worn by a legion of supermodels including Iman, Naomi Campbell, Helena Christensen, Carla Bruni, and Eva Herzigová.

Born in London to Irish parents, O’Brien grew up in Finglas and his journey into fashion was instinctual and unorthodox. An initial interest came through reading women’s fashion magazines, watching Hollywood movies and the inspiration of ‘glamorous’ women in his life, including his mother and aunts. He left school at 15 and while working in the men’s outfitters Bests on Dublin’s O’Connell Street, he discovered a talent for visual merchandising which led to a job in one of the city’s biggest department stores, Arnotts. He later moved to London and worked for Marshall & Snellgrove (now Debenhams).

O’Brien’s designs all originate as drawings. While working in London, he secured a place at Central Saint Martins as a mature student, on the basis of this strength. There, he completed a degree in Fashion Design (1979), followed by a post-graduate qualification in Fashion Illustration at Parsons School of Design, New York (1980).

O’Brien fell in love with Paris when he holidayed there as a 19-year-old and upon graduation he moved to the city. In 1981 he began working for Christian Dior, under the direction of Marc Bohan whose clients included Jacqueline Kennedy and Sophia Loren. O’Brien subsequently worked at Givenchy (1983-5), before becoming a design assistant to Guy Paulin at Chloe, the company that invented the concept of luxury ‘ready to wear’.

'THE ONLY IRISH FASHION DESIGNER TO HAVE CARVED A SUCCESSFUL CAREER IN HAUTE COUTURE PARIS'.

Within a year, Paulin had left and O’Brien became Head of Design at Chloe, remaining there for two years before he briefly moved back to New York. While in New York he was head-hunted by the perfume house Rochas, which was keen to re-establish the clothing line it had closed in 1955.

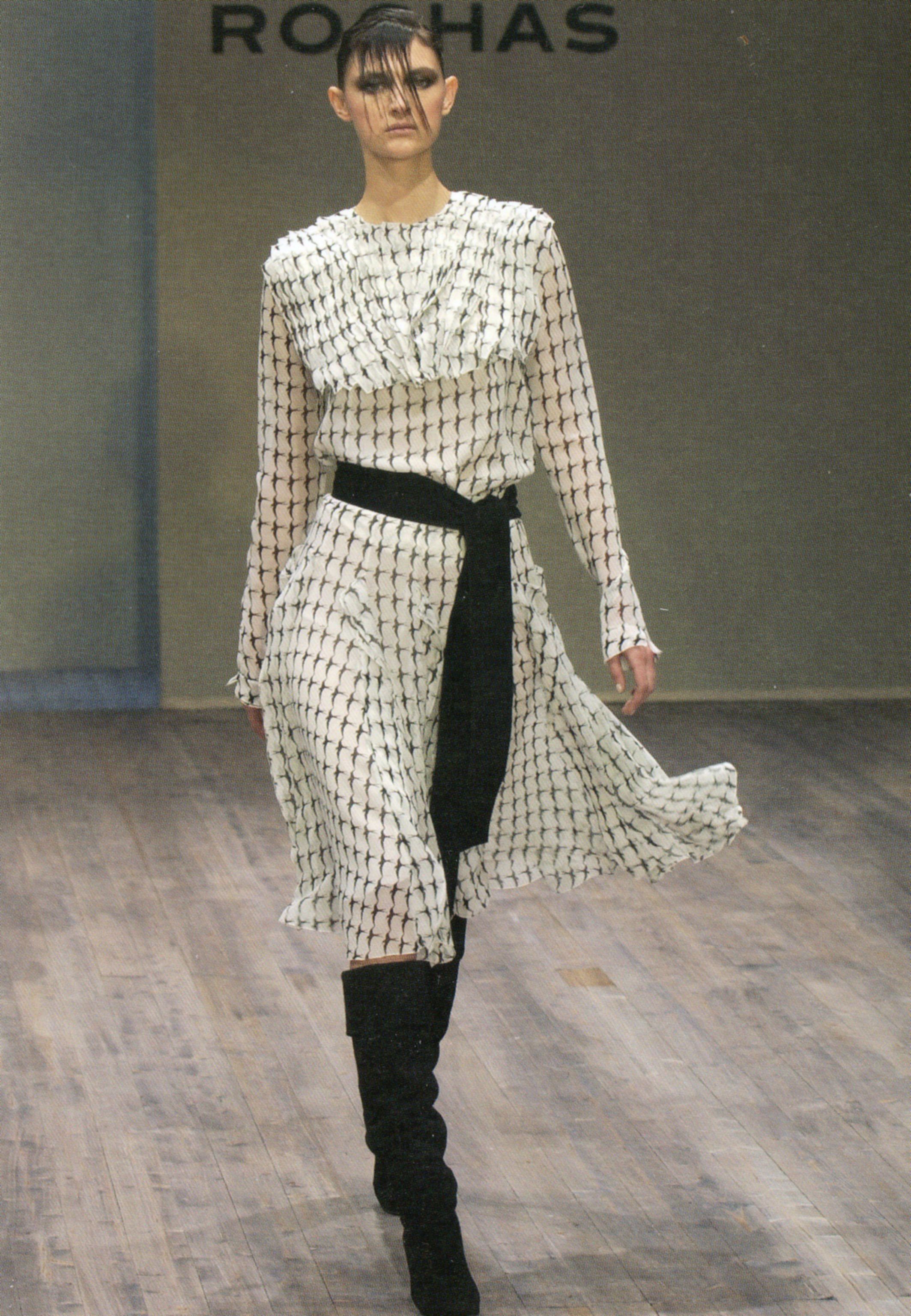

Rochas, Paris, 2003

Rochas, Paris, 2003

O’Brien was Director at Rochas for 12 years. He excelled in creating elegant, under-stated clothes ‘that whisper rather than shout’, inspired by the restraint and confidence of French women. One piece that featured in several collections was a full-length ‘ballskirt’. In 1995 Kristin Scott Thomas wore a striped version with a white denim jacket to the Cannes Film Festival, while the following year the French Rose of Tralee wore the skirt in dark blue with a cropped Aran sweater.

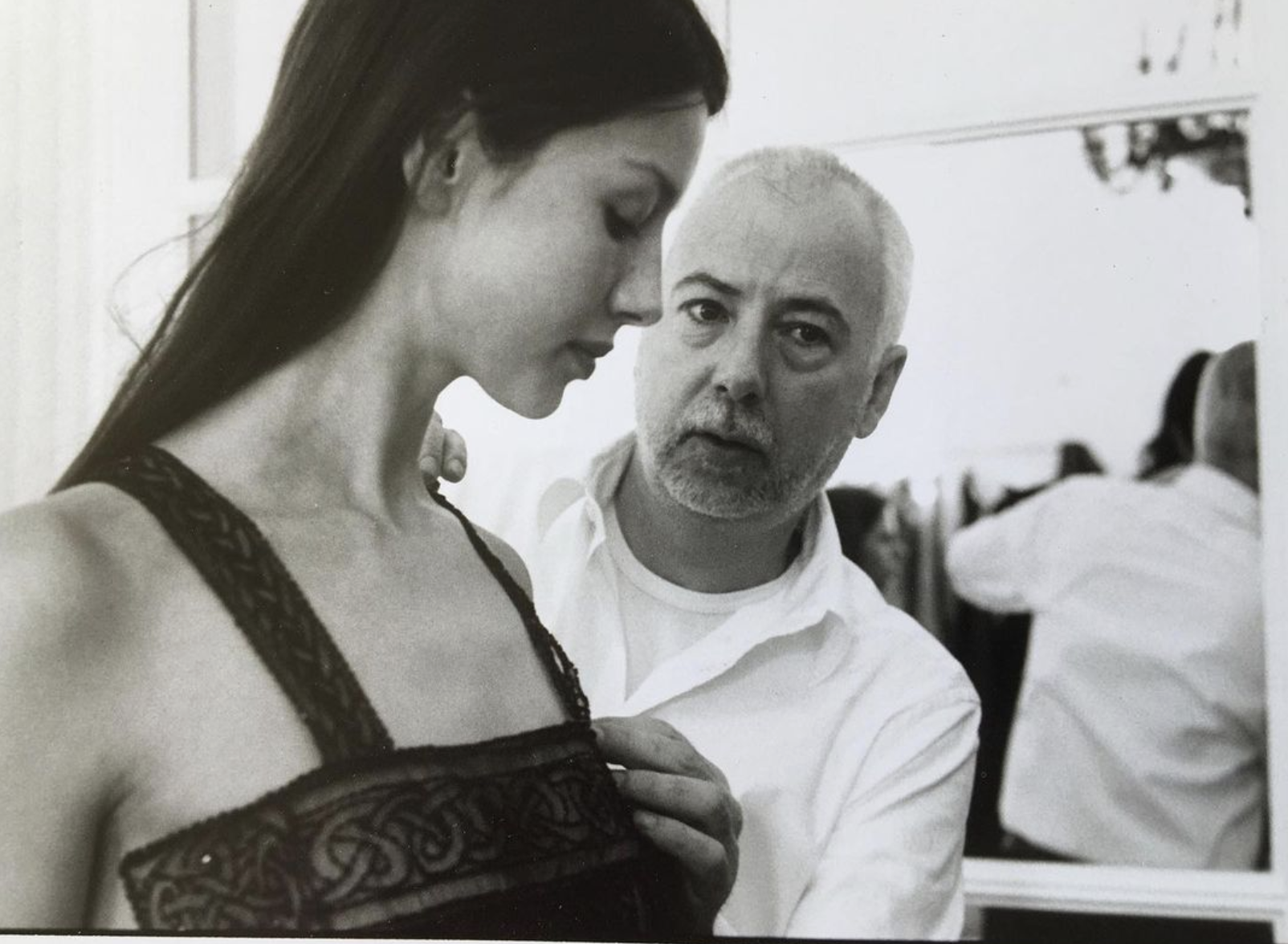

Celtic Embroidery, Haute Couture Collection, 2000

Celtic Embroidery, Haute Couture Collection, 2000

O’ Brien frequently incorporated references to Ireland into his Parisian work. These were particularly evident in the Peter O’Brien Haute Couture collection, shown at the Irish Embassy in Paris in 2000. This included Donegal Irish tweed, bejeweled Aran knits, green chiffon and embroidery inspired by Celtic interlacing.

Returning to live in Ireland in 2004, O’Brien brought his ‘quiet’, French-inspired clothes to wider audiences through collections for A-Wear (2006-9), Arnotts (2010-13) and the national retailer Dunnes Stores (2018-19).

Green blouse, Haute Couture Collection, 2000

Green blouse, Haute Couture Collection, 2000

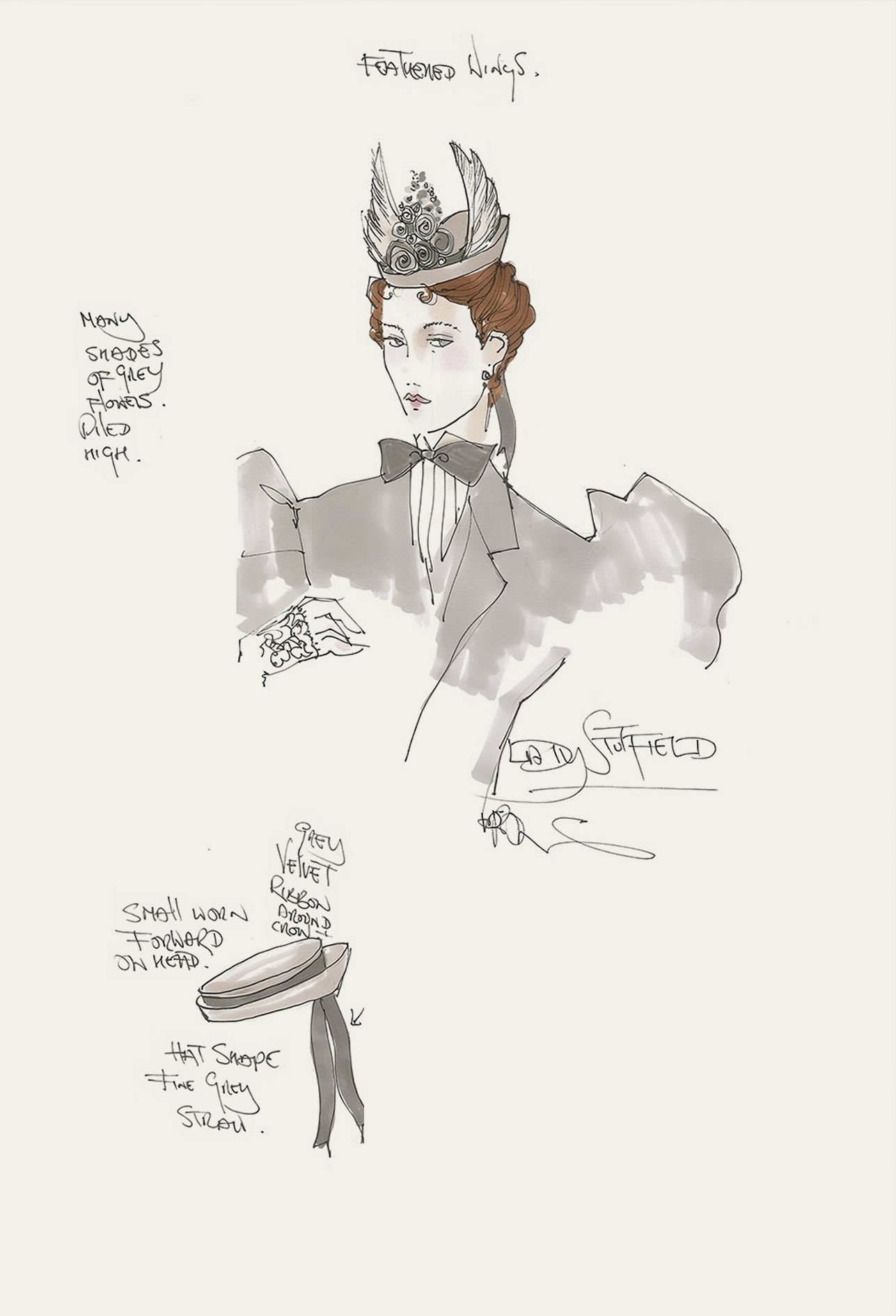

The move also enabled him to forge a new career as a costume designer: he has won many awards for his work at the Abbey, Gate and Project theatres, interpreting the works of Oscar Wilde, F Scott Fitzgerald, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Coward amongst others. He was the costume designer for the film Price of Desire (2013), a biopic about Eileen Gray and E-1027 and now lectures in Costume Design at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology (IADT), Dublin. Examples from Peter O’Brien Haute Couture (2000) can be found in the collection of the National Museum of Ireland and some of his drawings are held by the National Library of Ireland.

Sketch for A Woman of No Importance

Sketch for A Woman of No Importance

Costume from A Woman of No Importance

Costume from A Woman of No Importance

GRAFTON ARCHITECTS

The most prestigious international recognition for architecture is the Pritzker Architecure Prize. It ‘honor(s) a living architect or architects whose built work demonstrates a combination of… talent, vision, and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture’. In 2020, this prize was awarded to University College Dublin graduates Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara.

© The Daylight Awards

© The Daylight Awards

Farrell and McNamara co-founded Grafton Architects in 1978, the name of their practice referencing their first studio on Dublin’s principal shopping street, Grafton Street. Since then Grafton have excelled in the design of educational facilities, including campuses for the Università Luigi Bocconi in Milan (2008), the University of Limerick (2013), the New University Campus for UTEC in Lima (2015), Kingston University, London (2019) and in France: Toulouse School of Economics (2019) and Institut Mines-Télécom, Paris-Saclay (2019).

Temple Bar, Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Temple Bar, Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Grafton first gained wide-spread recognition as part of Group ’91, a consortium of thirteen young architects that made an ambitious pitch to develop Dublin’s Temple Bar during the city’s tenure as European City of Culture (1991). The area comprised a warren of buildings and streets dating from the 18th and 19th centuries and had been threatened with demolition. Group ’91 presented a detailed plan for the area with an emphasis on retaining and converting the buildings into cultural spaces, and adding some new buildings and public squares. Grafton designed Temple Bar Square (1996) opening up its neighbouring streets to easier public circulation and adding retail units and apartments.

Department of Finance. Photo: Dennis Gilbert

Department of Finance. Photo: Dennis Gilbert

In the years that followed, Grafton designed a number of key educational, civic and cultural spaces across Ireland, including many primary and secondary schools, an extension to Trinity College, Dublin (2006), new offices for the Department of Finance, Dublin (2007) and the Solstice Arts Centre in Navan, County Meath (2007).

THE MOST PRESTIGIOUS INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION FOR ARCHITECTURE IS THE PRITZKER ARCHITECTURE PRIZE... IN 2020, THIS PRIZE WAS AWARDED TO UCD GRADUATES YVONNE FARRELL AND SHELLY McNAMARA.

Universita Luigi Bocconi, Milan. Photo: Federico Brunetti

Universita Luigi Bocconi, Milan. Photo: Federico Brunetti

In 2008, the practice gained huge international recognition for the Università Luigi Bocconi in Milan. Grafton took inspiration from the architectural heritage of the city and the importance of the university to Milanese life, consciously connecting the building to its surrounding area. The same philosophy of site specificity and geographical reflection is evident in its recent work in France, specifically for university buildings in Toulouse and Paris.

THE CITY'S RICH HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION, COMBINED WITH ITS DISTINCTIVE ARCHITECTURE OF BRIDGES, WALLS, ARCHWAYS, COURTYARDS AND BRICKWORK, WERE KEY ELEMENTS USED TO INFORM THE NEW STRUCTURE.

The University of Toulouse was established in the 13th century. When Grafton won a competition to design its new School of Economics in 2009, the city’s rich history and geographical location, combined with its distinctive architecture of bridges, walls, archways, courtyards and brickwork, were key elements used to inform the new structure. The centre of the building is carved out as a courtyard, making use of the city’s temperate climate by allowing air to circulate through and around its offices and teaching spaces. A number of observation points and walkways – inspired by the city’s cloisters – ensure students and staff have a clear view of the city, the Garonne River and the surrounding landscape.

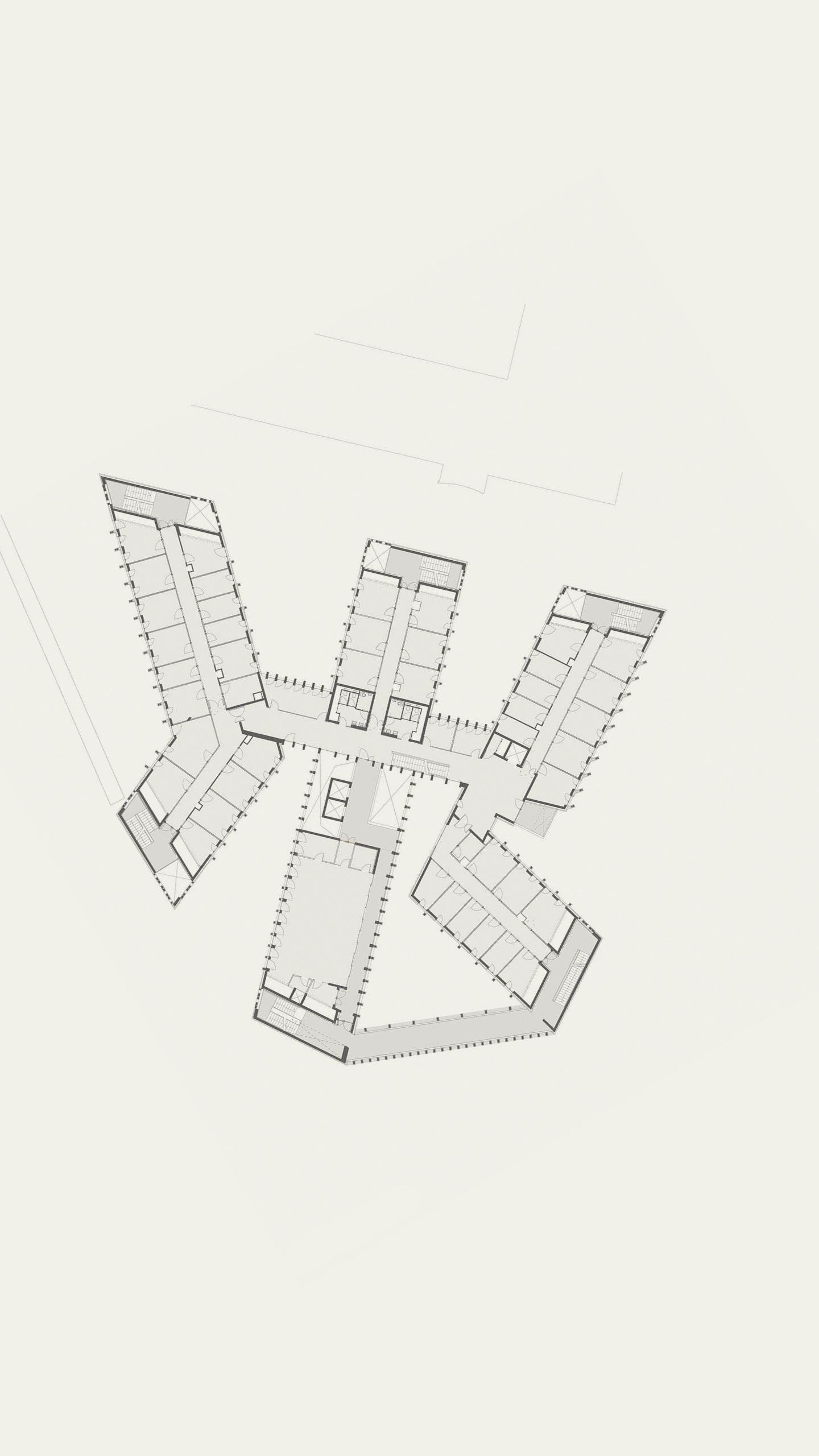

By comparison, the University of Paris-Saclay, is a new university. For its Institut Mines-Télécom, Grafton created new streets, squares and courtyards taking inspiration from the landscape and layouts of older universities including Oxford, Cambridge and Harvard.

Grafton have been awarded numerous accolades including the Mies Van der Rohe Award for excellence in EU architecture (2022). McNamara and Farrell also curated the 16th Architectural Biennale in Venice (2018). The practice recently completed new headquarters for the Electricity Supply Board in Dublin and is currently working on transforming the Odlums factory, at Dublin’s Port, into a cultural centre.

Toulouse School of Economics. Photo: Frédérique Félix-Faure

Toulouse School of Economics. Photo: Frédérique Félix-Faure

Institut Mines-Télécom, Paris-Saclay. Photo: Philippe Ruault

Institut Mines-Télécom, Paris-Saclay. Photo: Philippe Ruault

Institut Mines-Télécom, Paris-Saclay. Photo: Dennis Gilbert

Institut Mines-Télécom, Paris-Saclay. Photo: Dennis Gilbert

Yvonne Farrell & Shelley McNamara with EU Mies Award. Photo: Anna Mas

Yvonne Farrell & Shelley McNamara with EU Mies Award. Photo: Anna Mas

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With thanks to Clare McNamara at the National Museum of Ireland, Paula Stone at Grafton Architects and Peter O’Brien.