DESIGNING FOR IRELAND

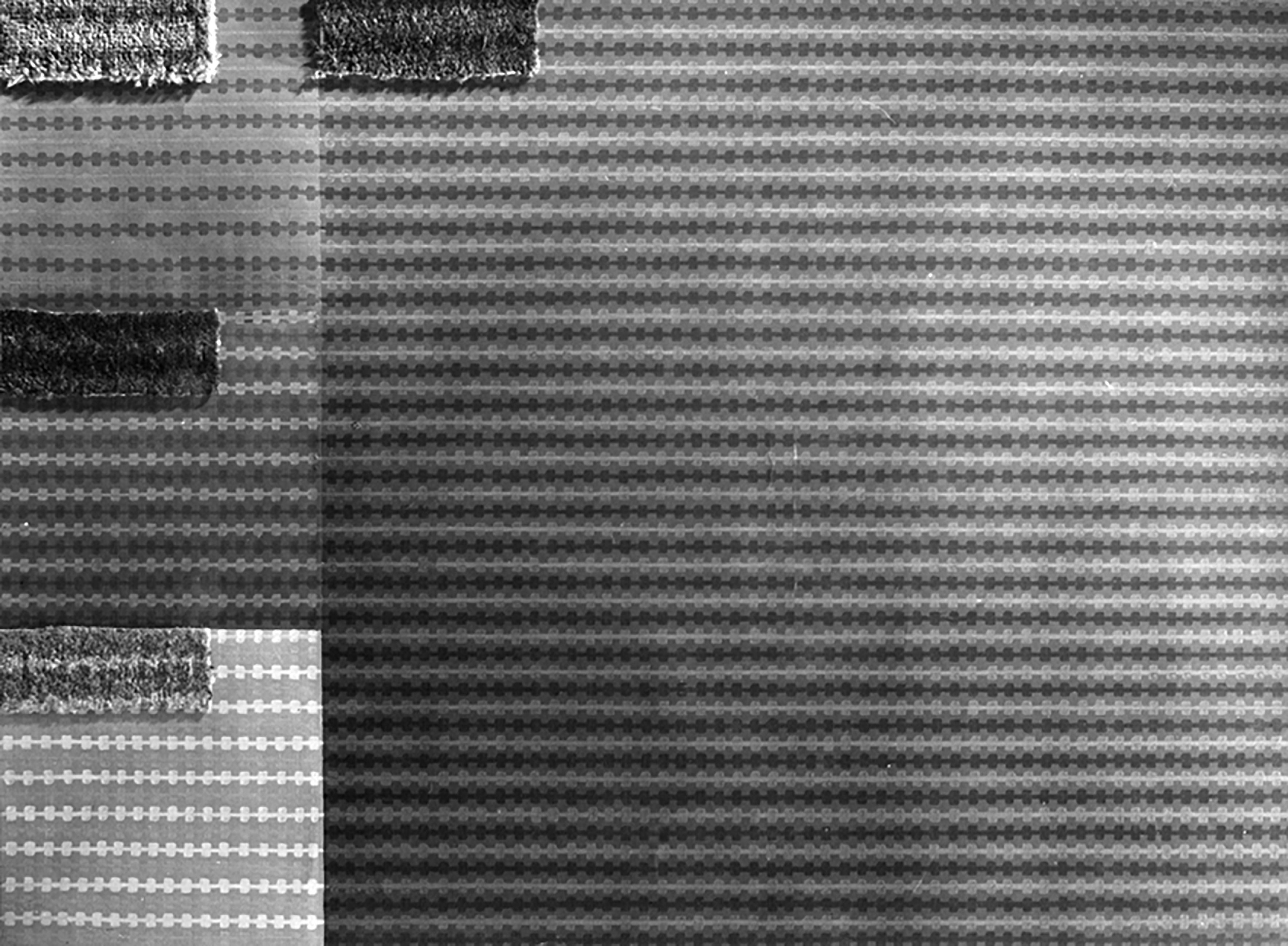

In 1922, before designs for new Irish postage stamps had been approved, British stamps already incirculation were overprinted with the Irish words - “Rialtas Sealadach na hEireann, 1922” (National Library of Ireland)

In 1922, before designs for new Irish postage stamps had been approved, British stamps already incirculation were overprinted with the Irish words - “Rialtas Sealadach na hEireann, 1922” (National Library of Ireland)

THE STORY OF KILKENNY DESIGN WORKSHOPS

Anniversaries matter. They allow organisations, states and societies the opportunity to celebrate significant milestones, to reflect on past experiences and achievements and to measure progress or otherwise across a defined stretch of time.

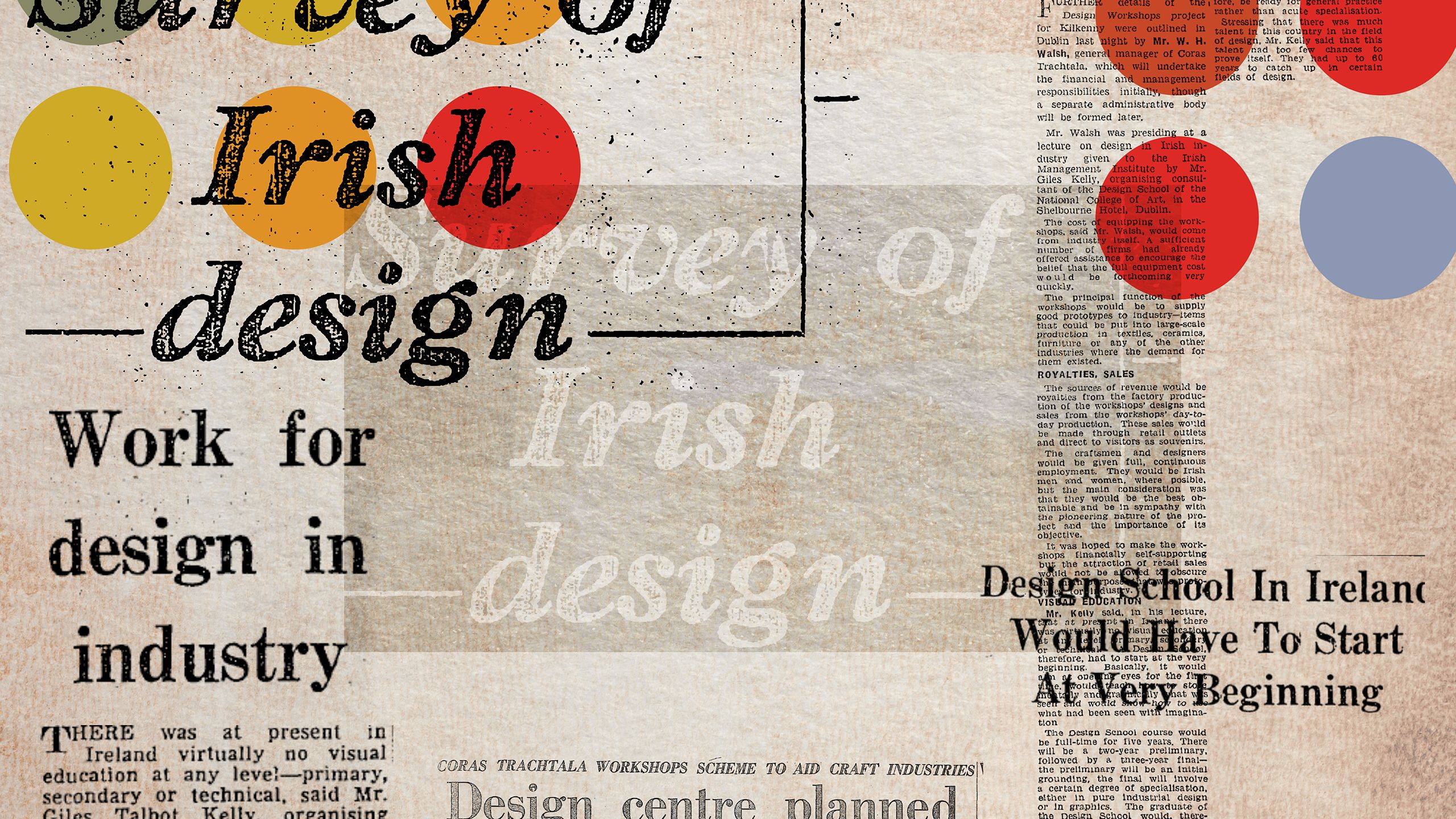

While 2022 most obviously marked the centenary of the creation of an independent Irish State, it also saw the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of a landmark report that had been commissioned by Córas Trachtála, a body established to promote exports and help lift the Ireland out of the economic and social quagmire of the middle decades of the 20th century.

Published in 1962, Design in Ireland, otherwise known as the Scandinavian Report, would act as a catalyst for a series of important State interventions intended to develop design awareness and better support Irish industry in producing quality products capable of competing in domestic and international markets. And Irish products would most certainly be called upon to compete. In the late 1950s, impelled by a series of crises of which a stagnating economy, high unemployment and soaring emigration were the most obvious markers, Ireland opted to break from long-established economic policies that were rooted in principles of protectionism and the idea of Irish self-sufficiency. Jettisoning these policies, Irelands inward gaze was turned outwards. What did this mean in practice? Politically, it meant taking the first steps towards membership of the European Economic Community (EEC). More immediately, however, it meant shifting the economic focus towards support for export orientated growth, the attraction of foreign investment and the embrace of free trade and open competition.

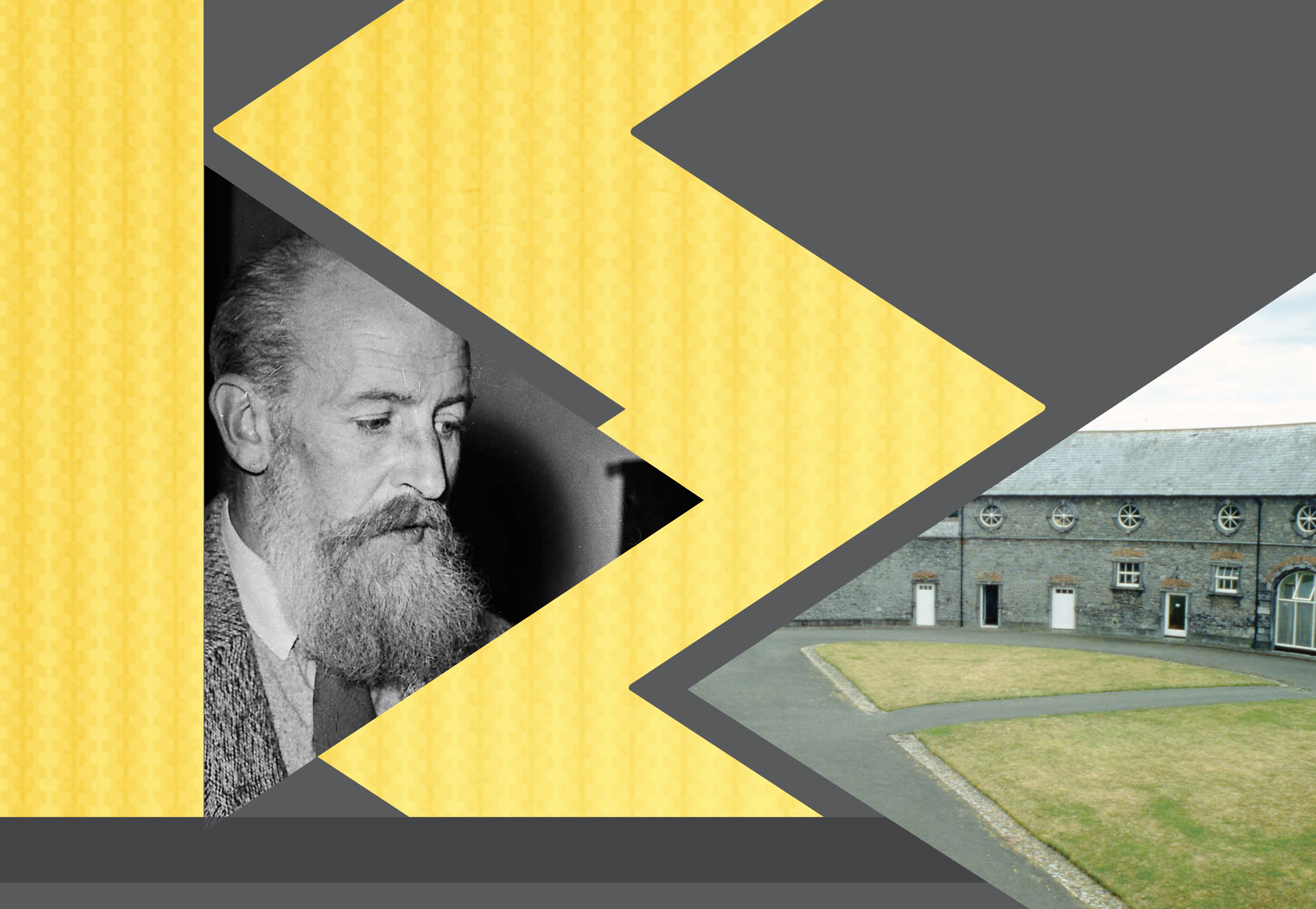

The establishment of Kilkenny Design Workshops (KDW) in 1963 was vital in preparing Irish industry to face these new competitive realities, while simultaneously addressing many of the design deficiencies highlighted in the Scandinavian Report. KDW would enjoy a relatively short yet illustrious lifespan: over a twenty-five year period, from its base in a beautifully renovated Courtyard adjacent to the historic Kilkenny Castle, it led the national effort to promote and develop design standards.

Prototypes and design solutions were provided to Irish and foreign-owned firms; training was offered to young Irish and international designers; exhibitions were mounted; and shops were opened to showcase, in Ireland and beyond, the best of Irish-designed and manufactured products. KDW was at once a pioneering and progressive enterprise: the first government sponsored design agency in the world, it would, long after its demise, still be credited as the single, most important design initiative in the history of the state.

TIMELINE

1951

Arts council is established. Remit includes responsibility for 'design industry'.

1952

Corás Trachtála is established as a semi-state body to promote and develop Irish exports.

1954

Arts Council supports, and Design Research Unit of Ireland produces, an International Design Exhibition which is staged in Dublin and Cork.

1956

Irish Design Exhibition launches in Dublin before touring to Waterford, Cork, Limerick, Galway and Sligo.

1958

Irish Packaging Institute established.

Bill Walsh, general manager of Córas Tráchtála (1964)

Bill Walsh, general manager of Córas Tráchtála (1964)

1960

Coras Tráchtála (CTT), the Irish Export Board, is entrusted by Government with responsibility for the improvement of standards of industrial design. Jack Lynch, then Minister for Industry and Commerce, expresses the hope that the group’s recommendations would provide the basis for a full scale programme of industrial design development. Institute of Creative Advertising and Design is founded.

William Walsh and Jim King, pictured on either side of Taoiseach Jack Lynch and Minister George Colley, c. 1966 ('The Tom Brett Collection, Kilkenny County Council and Kilkenny Archives’)

William Walsh and Jim King, pictured on either side of Taoiseach Jack Lynch and Minister George Colley, c. 1966 ('The Tom Brett Collection, Kilkenny County Council and Kilkenny Archives’)

1961

Coras Tráchtála sets up its own design section and commissions a survey by the Scandinavian Design Group. Five designers – three Danes, a Swede and a Finn – spend over two weeks in Ireland in April 1961 examining what was being done in factories, workshops, schools and training colleges.

1962

Design in Ireland, also known as the ‘Scandinavian Report’, is published and William Walsh, general manager of CTT, travels to the Plus Workshops in Fredrikstad, Norway.

1963

William Walsh informs meeting of Kilkenny Chamber of Commerce of plans to establish workshops that would have as their “principal function the production of well-designed prototypes for industry”. Announces also that design centre will be located in Kilkenny Castle yard.

In September, Minister for Education, Dr. Patrick Hillery, appoints a Council of Design, chaired by Dr. Michael ffrench O’Carroll and including William Walsh. It holds its inaugural meeting on October 31, 1963.

Afzelia Bowls designed by one of Finland’s most internationally renowned designers, Bertel Gardberg, 1966.(Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

Afzelia Bowls designed by one of Finland’s most internationally renowned designers, Bertel Gardberg, 1966.(Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

1964

A two-week, residential seminar on textile design is organised under the auspices of KDW – the first of its kind in Ireland. The seminar, held in June, is led by renowned Swedish designer and teacher, Fru Edna Martin, with the aim to “inspire and build an awareness of the special character which Irish textiles as a whole can develop”.

1965

Council of Design submits report to Government in September. The principal recommendations concern the creation of a permanent and autonomous National Design Council which should, in turn, establish a new National College of Art, Architecture and Design. It takes more than a year before the report is published and not all of its recommendations are supported in Government – principally the establishment of a new College, a decision on which is deferred pending a report of a Commission on Higher Education.

In November 1965, KDW is formally opened by Dr. Patrick Hillery, Minister for Industry and Commerce.

A tableware display from the 1960s. ('The Tom Brett Collection, Kilkenny County Council and Kilkenny Archives)

A tableware display from the 1960s. ('The Tom Brett Collection, Kilkenny County Council and Kilkenny Archives)

1966

27 year-old Jim King is appointed general manager of Kilkenny Design Workshops.

A new design scholarship, worth £500 per annum and sponsored by Associated Electrical Industries (Ireland) Ltd is launched. Open to students across the island and with a prize of one year’s study at KDW, the first winner is Eleanor Collen of Tandragee, Co. Armagh.

First Kilkenny shop opens.

First annual Christmas Fair is held.

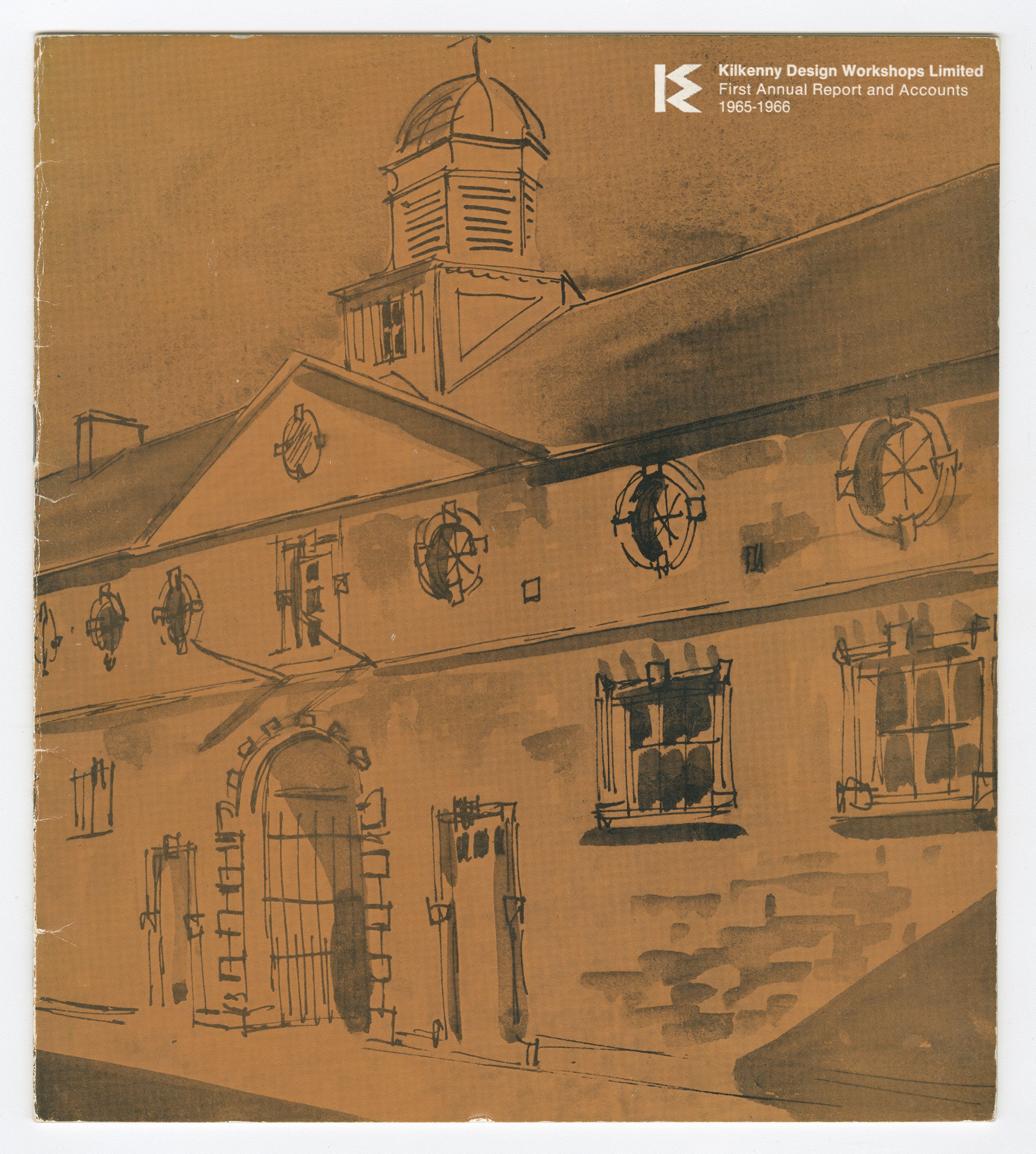

1967

First annual report of KDW, covering 1965-66, is published. Kilkenny People hails the development as ‘a major breakthrough not only for the Kilkenny Design Centre where the prototypes were produced, but also for the Irish export industry.’

1969

An exhibition, Design for Production , opens in Kilkenny. Deputy Secretary of the Department of Industry and Commerce says the products on display were “message-carriers of a new outlook on Irish industry.” William Walsh warns, however, that design is a “not a sort of magic that will compensate for deficiencies in all other directions”. (Nationalist and Leinster Times, 14 Nov 1969)

1971

Two Georgian buildings adjoining the workshop and known as Butler House are purchased by KDW. Butler House is intended for use as residential accommodation for graduate designers and as conference facilities.

Crafts Council of Ireland is established to take responsibility for non-industrial handicrafts.

1972

Society of Designers in Ireland (later the Institute of Designers in Ireland) is formed as a professional body representing the interests of Irish designers. It would later confer honorary life membership on KDW founder, William Walsh.

Kilkenny Shop is expanded from 140 to 250 sq. metres.

1973

Ireland becomes a member of the EEC.

KDW undertakes survey of need for design services by Ireland’s engineering industries.

Council for Industrial Design is established with objective to report and make recommendations to inform a national design policy.

KDW undertakes survey to ascertain demand for design services in engineering sector

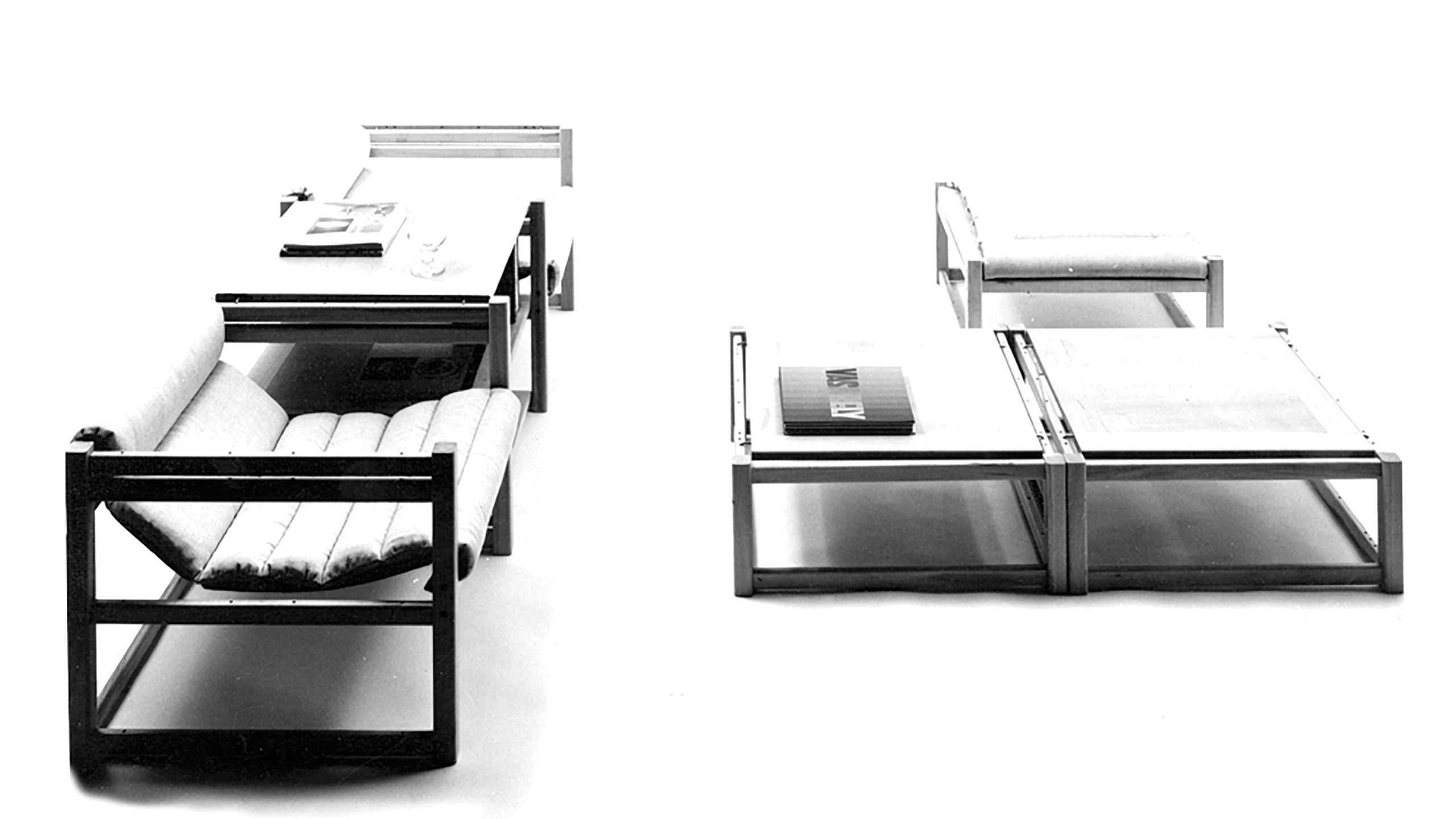

Section chair system

Section chair system

1974

KDW relationship with Corás Trachtála ends as it becomes the direct responsibility of the Minister for Industry and Commerce.

First-ever Kilkenny Arts Week is staged – KDW contributes a show on three hundred years of Irish silver.

1975

Council of Industrial Design report, Guidelines for a National Industrial Design Policy is completed. It is still not published by 1978.

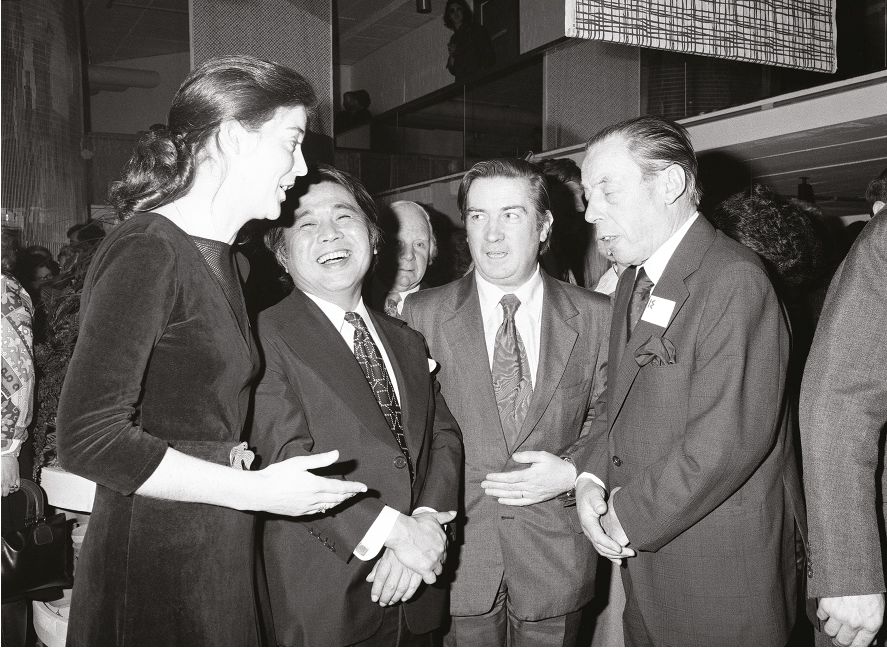

Mary Mullin, Kenji Ekuan (President of ICSID), Minister Justin Keating and W.H. Walsh at opening ofKilkenny Shop, Dublin, 1976. (Irish Photo Archive)

Mary Mullin, Kenji Ekuan (President of ICSID), Minister Justin Keating and W.H. Walsh at opening ofKilkenny Shop, Dublin, 1976. (Irish Photo Archive)

1976

KDW opens a second retail shop on Nassau Street, Dublin. It is financed entirely on borrowed money.

Miss Mary V. Mullin, who joined KDW in 1967, is elected the first woman vice-president on the board of the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID), a body representing about 10,000 professional designers in 36 countries.

NCAD offers Ireland’s first degrees in industrial design – the first graduates are conferred in 1980.

1977

Butler House is officially opened after a £370,000 renovation. Jubilee Congress and general assembly of the International Congress of Industrial Design is held in Ireland. (September) An exhibition featuring work from 14 artists is staged in the Kilkenny Shop in Dublin run for the duration of the conference. KDW sponsors the first Irish Book Design Award.

1978

KDW assumes overall responsibility for the promotion and development of industrial design – CTT continues to service the marketing and other needs of exporters. KDW is also charged with advising the Minister for Industry, Commerce and Energy on all matters relating to the improvement of industrial design.

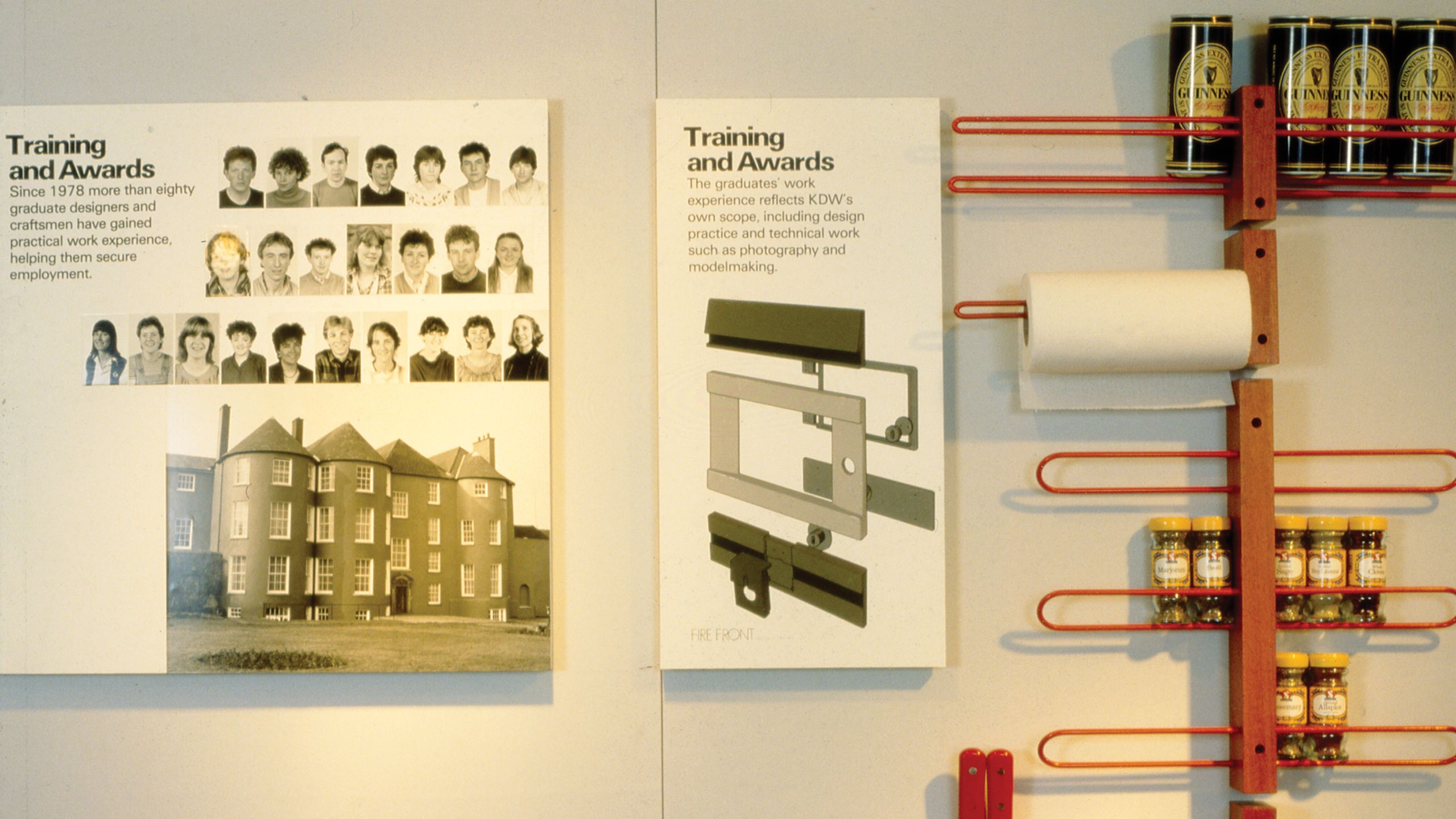

Designer training project based at Butler House comes into full operation, aided by a £28,400 annual grant from the Europeacial Fund. Ten trainees spend an average of six months at the Workshops during the year.

1979

New floor opened in Kilkenny Shop, Dublin, devoted to furniture and furnishing

1981

Half a million people visit Nassau Street shop and turnover reaches £1.3m. In the same year, however, an internal Government briefing document states that KDW was under ‘considerable financial strain at the moment due largely to the rapid expansion of its retail services.’

1982

Kilkenny Design Workshops Limited Bill, 1982, allows for the Minister for Finance to take shares of £500,000, in order to reduce the Company’s borrowings. KDW debts are almost entirely associated with its purchase of the Dublin shop.

Following the death of Sir Basil Goulding, Dublin-based accountant, Margaret Downes is appointed the new Chairman of KDW – she is the first woman to head a commercial semi-state company.

1984

21st anniversary of KDW is marked by the publication of a commemorative book and the hosting of a major exhibition in Dublin. Held in November, ‘Kilkenny Design: 21 years of Design in Ireland’ attracts approximately 20,000 visitors.

1985

Board of KDW presents, and the Irish Government approves, a programme to lead KDW to full commerciality.

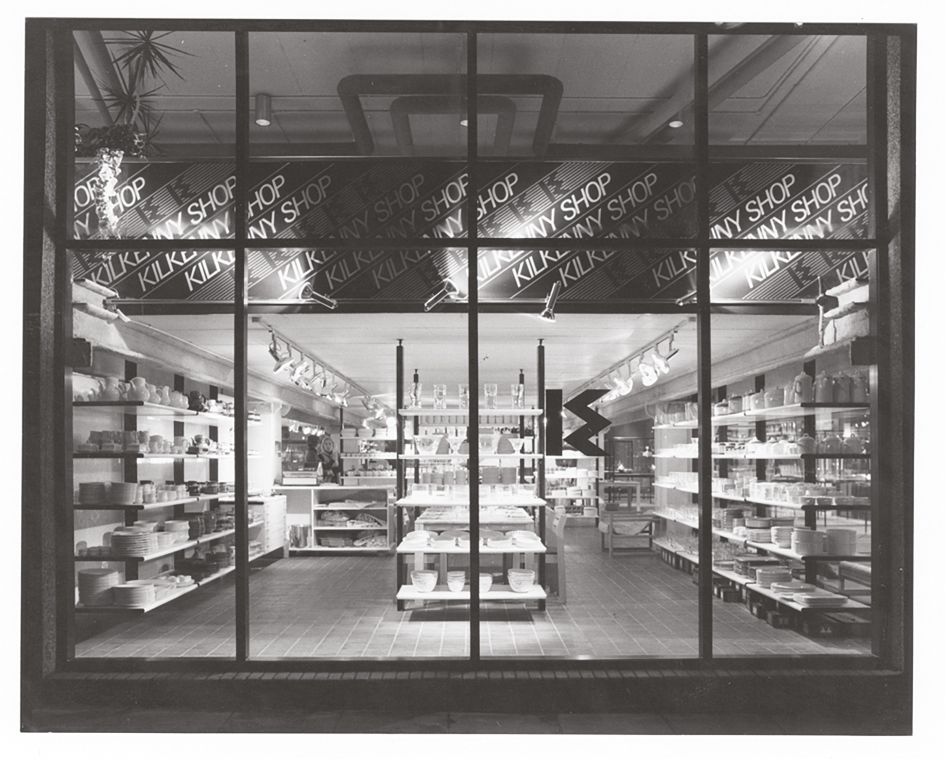

Exterior view of the Kilkenny shop, London, 1986 (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

Exterior view of the Kilkenny shop, London, 1986 (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

Interior view of the Kilkenny shop, London, 1986(Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

Interior view of the Kilkenny shop, London, 1986(Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

1986

Official opening by An Taoiseach, Garret Fitzgerald, of Kilkenny Design Shop at Ireland House, Bond Street, London.

1987

Chief Executive of KDW, Pat Henderson, resigns on 31 October 1987. After 22 years with KDW, Henderson leaves to take a role in private industry.

In November, Albert Reynolds, Minister for Industry and Commerce, informs the Dáil that the ‘phased’ elimination of grant-in-aid to KDW is intended to allow it implement measures to achieve ‘full commerciality’.

Preliminary accounts for the same year were nevertheless expected to show a loss of £449,000.

1988

Government decides on the ‘orderly wind down’ of KDW.

Once the fate of KDW is decided, attention immediately turns to the future of Butler House.

In November, Minister for Industry and Commerce seeks Government approval for a Kilkenny County Council proposal to hand over KDW complex in Kilkenny, including Butler House, to Kilkenny Civic Trust.

21st Century

2001

KDW archive is donated to the National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) by the Crafts Council of Ireland.

2005

As Cork becomes European City of Culture,the Crafts Council of Ireland commissions a retrospective exhibition on Kilkenny Design Workshops (KDW). It is titled Designing Ireland

2015

Fifty years after the opening of KDW, the Irish Government holds Irish Design 2015, a year-long programme of events to emphasise the importance of design to success in business and as a ‘catalyst of change’. An app is produced for the occasion to recognise the KDW’s impact on design in Ireland and beyond.

2022

Sixty years after the publication of the Scandinavian Report, Design in Ireland, its impact on public policy provision and the subsequent contribution of KDW to Irish design development is revisited in Kilkenny. A half-day conference, Design Kilkenny: Past, Present + Future , is held to reflect on the legacy of KDW and the future of Irish design.

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT IN IRELAND

The story of design in independent Ireland did not begin with the publication of Design in Ireland or the establishment of KDW the following year. It began at the birth of the new Irish State when design was deployed as a means of visually signalling a break from Britain and the transfer of administrative and political power into Irish hands. It started with a series of stamps, the designs of which were purposely political, and it continued with the striking of new coinage which acted, Nobel laureate poet W.B. Yeats adjudged, as silent ambassadors of national taste. Yet, despite these symbolically significant initiatives, the importance of design did not register deeply at either popular or policy levels in the formative decades of the new State.

William H. Walsh, who, as general manager of Córas Tráchtála, was the driving forcebehind the establishment of KDW. Walsh later served as Chief Executive and Chairman of KDW. (RTÉ Archives)

William H. Walsh, who, as general manager of Córas Tráchtála, was the driving forcebehind the establishment of KDW. Walsh later served as Chief Executive and Chairman of KDW. (RTÉ Archives)

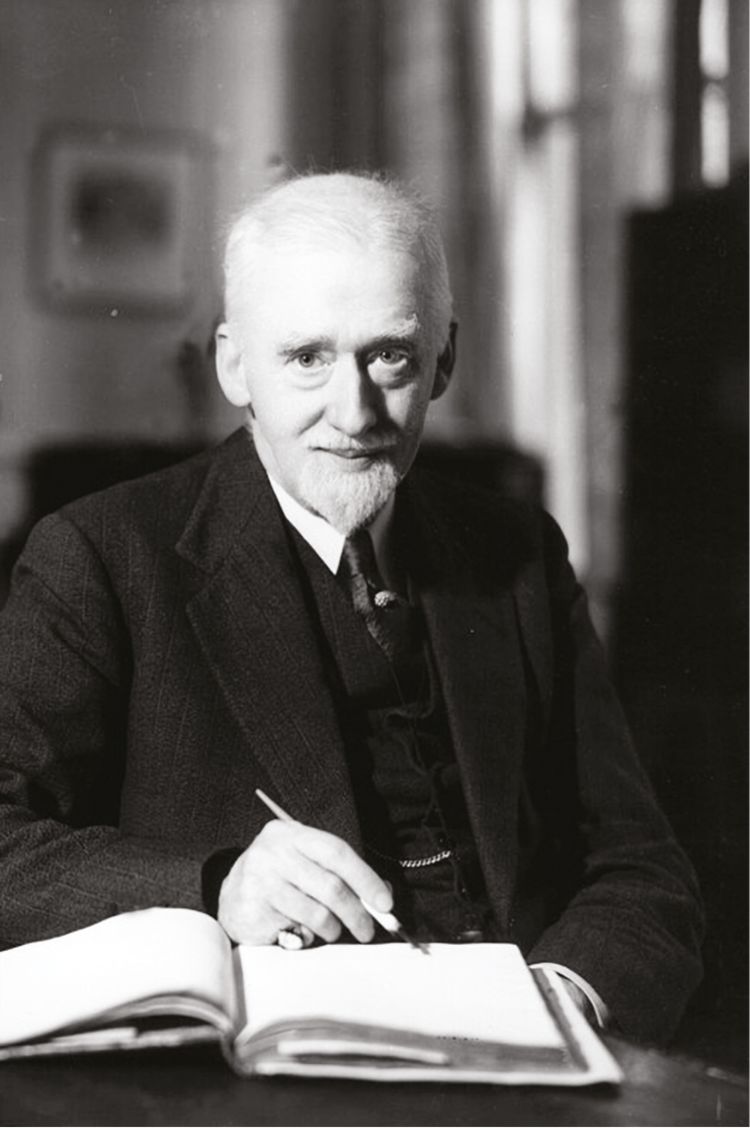

Dubliner Thomas Bodkin, a qualified barrister, art critic and Director of the National Gallery of Ireland from 1927 to 1935, was a key advocate for change. Throughout the first decade of what was then the Irish Free State, he encouraged Government to actively promote a closer relationship between industry and up-to-date instruction in design. Nothing came of Bodkins early efforts, but he would later be instrumental in effecting policy progress through his authorship of a Government commissioned report that led, in 1951, to the setting up of an Arts Council with legislative responsibilities that extended to design in industry. In the years that followed, a poorly funded Arts Council organised a number of design exhibitions, provided small grants to firms to cover the employment costs of a designer and introduced the countrys first industrial design scholarship.

Dubliner Thomas Bodkin was a key influence on the development of cultural policy in the formative decades of the Irish State. It was Government-commissioned and Bodkin authored report that led to the establishment in 1951 of an Arts Council, with a remit extending to ‘design in industry’. (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

Dubliner Thomas Bodkin was a key influence on the development of cultural policy in the formative decades of the Irish State. It was Government-commissioned and Bodkin authored report that led to the establishment in 1951 of an Arts Council, with a remit extending to ‘design in industry’. (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

However, after failing to forge the desired links to industry or influence a significant improvement in design standards, the Department of Finance moved in 1960 to transfer responsibility for industrial design from the Arts Council to Córas Tráchatála (CTT), a semi-state body established eight years prior with a mission to develop Ireland's export potential. It would prove to be a transformative decision. Led by William H. Walsh, CTT set up its own design section and invited a team of Scandinavian experts to provide an authoritative and impartial assessment of where Ireland stood in relation to design. When published in February 1962, their findings made for predictably dismal reading. The Scandinavian Report — Design in Ireland — was unflinching in its criticisms of Irish visual education and design standards. However, nowhere was the harshness of the visitors verdict more obvious than in their assessment of Irish products, a range of which were found to be so badly designed and executed that they would not have the slightest chance of competing successfully on the world market.

HOW KDW STARTED

Design in Ireland created a serious stir. Taoiseach Seán Lemass would later remark that the report generated more debate and radiated greater awareness of industrial design than all the exhortations of Ministers and Art Councils and others had succeeded in doing up to that. But to what effect? The Scandinavian group had impressed the urgency of action and made a series of recommendations which amounted to what academic John Turpin considered to be a manifesto for modernism. But while it undoubtedly acted as a catalyst — the report had called for new body to be established - the origins of KDW owed less to any of these recommendations than to a visit by a CTT delegation to Norway later that year. Fronted by William Walsh, the delegates travelled to the PLUS Applied Art Centre in the historic town of Fredrikstad, fifty miles south of the capital of Oslo. Here was situated a unique, nonprofit organisation that, under the guidance of Per Tannum, had brought together designers, craftsmen and producers in planned co-operation to develop models and patterns for industrial reproduction.

Inspired by what he saw, William Walsh immediately set about finding a suitable location for something similar in Ireland. He found it in the south-east, in the Ormonde stables turned grain-stores opposite the historic Kilkenny Castle. Although in a state of disrepair, Walsh immediately saw the potential of the site: The buildings, he remarked, are spacious and with some alterations will be admirably suitable, as well as being, in themselves, a fine example of good design.

A spiral-shaped bracelet designed by German-born, Rudolf Heltzel, 1966. Heltzel joined the workshops in the mid-1960s and subsequently established his own business in Kilkenny. (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

A spiral-shaped bracelet designed by German-born, Rudolf Heltzel, 1966. Heltzel joined the workshops in the mid-1960s and subsequently established his own business in Kilkenny. (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

It was to a meeting of Kilkenny Chamber of Commerce in January 1963 that Walsh announced plans to establish workshops that would have as their principal function the production of well-designed prototypes for industry. The local reaction was one of delight and it was predicted that it would not alone revolutionise the tourist industry in Kilkenny, but the whole reputation of the city.

Afzelia Bowls designed by one of Finland’s most internationally renowned designers, Bertel Gardberg, 1966.(Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

Afzelia Bowls designed by one of Finland’s most internationally renowned designers, Bertel Gardberg, 1966.(Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

The conversion of the Castle courtyard would take two years to complete, yet there was little delay to the recruitment of the appropriate crafts-persons and designers. A silversmithing workshop was the first to open in 1963 under the leadership of Michael Hilliar — KDW's first employee — and others followed. By the time the Castle yard was renovated for a formal opening in November 1965, five separate workshops were up and running, focussing on woven textiles; printed textiles; ceramics; candle-making; silver and wood-turning - many of them led by foreign designers who would settle permanently, and set up enterprises of their own, in Kilkenny.

EVOLUTION AND EXPANSION:

KDW IN THE 1970s

The story of KDW in the 1970s was one of physical expansion and organisational evolution.

Beginning as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Corás Tráchtála, KDW was transferred to the control of the Minister for Industry and Commerce in 1974 and four years later, in 1978, it assumed overall responsibility for the promotion and development of industrial design. It was also specifically charged with advising the Minister on all matters relating to the improvement of industrial design.

These organisational changes occurred during a period of transition that saw KDW evolve away from primarily supporting craft-based industries towards a deeper involvement with those associated with engineering.

Designing for engineering-based products presented challenges of a different magnitude to those of other sectors - the designs, KDW acknowledged, needed to measure up to a more demanding criteria. To meet these criteria, a new department of industrial design for consumer goods and light engineering was established under the direction of Nick Marchant, its time-consuming, technical work encompassing everything from electronics to solid fuel stoves, optical equipment and energy saving appliances .The impact of this department was considerable: it would account by the end of the decade for more than 50% of the practical design services KDW provided to manufacturers.

Taoiseach Jack Lynch at the signing ceremony of the accession treaty of Denmark, Ireland, Norway and the United Kingdom, 22 January 1972, at Egmont Palace, Brussels. A special, Kilkenny-designed silver medal was later presented to officials involved in Ireland’s EEC accession negotiating team. (European Commission)

Taoiseach Jack Lynch at the signing ceremony of the accession treaty of Denmark, Ireland, Norway and the United Kingdom, 22 January 1972, at Egmont Palace, Brussels. A special, Kilkenny-designed silver medal was later presented to officials involved in Ireland’s EEC accession negotiating team. (European Commission)

Changes at KDW were a mirror of those more widely occurring: this was a decade when Ireland finally joined the EEC (in 1973) and when it acquired a series of new design-focussed organisations - the Crafts Council of Ireland in 1971 and the Society of Designers in Ireland in 1972. KDW was instrumental in the emergence of both, and when the National College of Art was legislatively reconstituted as the National College of Art and Design (NCAD), KDW established a close relationship with it too - the workshops providing a bridge between the worlds of academia and industry.

The centre of KDW’s training and education activities was Butler House, an 18th century property adjoining the workshops that was in need of refurbishment. Acquired by KDW in 1971, the renovation of Butler House ran overtime and over budget and left KDW with a hangover debt, yet when complete it greatly enlarged the number of annual residential vacancies for trainee designers.

The operational costs of Butler House were part funded by the European Social Fund and its opening in 1977 came just in time for Ireland’s hosting of the jubilee congress and general assembly of ICSID (International Council of Societies of Industrial Design), which represented some 10,000 professional designers across 36 countries.

Senior KDW personnel were enthusiastic contributors to ICSID, among them Mary Mullin, who had previously earned the distinction of being elected the first woman vice-president of its board. If her election was a measure of the growing international prestige of KDW, it was not the only one. Increasingly, KDW expertise was sought out overseas and the Kilkenny experience was used to inform United Nations programmes for developing countries.

Butler House, an 18th century property adjoining the workshops that was purchased and renovated by KDW in the 1970s. (Image courtesy of Kilkenny Civic Trust)

Butler House, an 18th century property adjoining the workshops that was purchased and renovated by KDW in the 1970s. (Image courtesy of Kilkenny Civic Trust)

RETAIL THERAPY:

SHOPPING AT KILKENNY DESIGN

Shops were never envisaged in the founding mission of KDW, yet they acquired over time a critical role in the promotional and funding activities of the Company.

A small Kilkenny shop was opened in 1966 and the following year the first generation of Kilkenny-designed products began to be promoted in both B. Altman's Fifth Avenue department store in New York and at Heals, a famous furniture and household goods store in London. These developments were nevertheless more about marketing and promotion than revenue generation. The reason for this was a straightforward one: there was an appreciation that retail sales, while clearly a feature of KDW financing and a means of protecting against too big a gap opening up between the drawing board and the processes of industry, should not deflect from the core business of providing prototypes to industry.

But the role of retail transformed with the opening of a large Dublin shop in 1976. Located as part of the newly built Setanta Centre on Nassau Street, the shop was funded entirely by borrowing on the part of KDW. Government approval was sought and given for this borrowing on the basis that the new shop would not be loss making.

A brochure promoting ‘Ireland House’, the Córas Tráchtála-leased building where KDW opened its short-lived shop in November 1986.

A brochure promoting ‘Ireland House’, the Córas Tráchtála-leased building where KDW opened its short-lived shop in November 1986.

The Nassau Street outlet aimed at the higher end of market. Fashion goods and very cheap things are out, the store's marketing manager remarked. We're providing for the planned purchase of solid and functional, but essentially attractive things. From the outset it was decided that the shop would not be exclusively stocked by the products of KDW projects, but would broaden to encompass the best of Irish designed and produced goods, whatever their source — a Kilkenny Selection label being used to distinguish brought-in merchandise from that originating with KDW.

The expansion of retail activities was not without its problems. Although the Nassau Street shop helped drive footfall and sales - in 1981 alone, over half a million people visited the premises and turnover reached £1.3m - it also caused borrowings to soar. The consequent strain on KDW's finances necessitated legislation to allow the Minister for Finance to take a £500,000 equity stake in the Company. The effect of the Kilkenny Design Workshops Limited Bill, 1982, was to reduce borrowings on the Dublin shop and enable £100,000 in outstanding loans on the Butler House conversion to be paid off.

Politically, the government's equity injection in KDW was uncontroversial and the legislation passed through the Oireachtas with ease. This was recognition of the importance of the work of KDW, but also, given the Company's radically transformed funding model, of the importance of retail to the continuation of that work. By 1985, the Government grant accounted for just 17% of KDW income; in contrast, revenues from the shops in Dublin and Kilkenny accounted for 70%. A push towards even greater commerciality was planned by KDW when it announced the opening of a new shop in London - its first full retail venture outside Ireland. Prestigiously located on New Bond Street in a Coras Trachtála-leased building known as Ireland House, a Government memorandum noted that the Kilkenny shops role would now be extended as an export show-place for high quality Irish products

Exterior view of the Kilkenny shop, London, 1986 (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

Exterior view of the Kilkenny shop, London, 1986 (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

CRISIS AND CLOSURE

The London shop opened in November 1986 to considerable optimism. The importance of the venture was underscored by the presence of the Taoiseach, Dr. Garret Fitzgerald, who declared the decision to locate in London to be an obvious first step in Kilkenny's quest to open new markets for suppliers and generate new income. Geography and history had made it so of course, yet as Fitzgerald presented it, the opening of the London outlet carried a significance that went beyond even vital concerns of commerce. To us in Ireland, he remarked, the opening of a Kilkenny Design shop in London is not just a profitable expedient; it is also symbolic of our confidence in our young people and enterprising designers and in what they are doing for our traditional industries and crafts.

This confidence would prove misplaced. The late in the year opening of the London shop cost the Company valuable tourist business and plunged it into financial trouble at a time when retail sales in its Irish shops were starting to slump, as local recessionary pressures began to bite. Far from being a driver of revenues therefore, KDW's retail activities helped dig it deeper into debt. The shops became, as one senior civil servant commented in early 1988, a continual drain on the company.

A training and awards display showing information about the Designer Development programme based at Butler house. The display highlights the success of graduate designers and craftsmen in securing employment on the back of the practical experience gained at KDW. (Collection National Irish Visual ArtsLibrary (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

A training and awards display showing information about the Designer Development programme based at Butler house. The display highlights the success of graduate designers and craftsmen in securing employment on the back of the practical experience gained at KDW. (Collection National Irish Visual ArtsLibrary (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

The Company's financial problems mirrored those of the country at large. Carrying echoes of an earlier era, high unemployment and soaring emigration returned in the 1980s amidst a crisis in the public finances. To address the latter, a new Charles Haughey-led government embarked on a course of fiscal retrenchment in 1987, intent on drastically cutting public expenditure and borrowing. It was a policy that involved the closing down or amalgamation of a number of State agencies. KDW was not one of them. Instead, the Government signalled its phasing out of all grant-aid by 1991, helping the KDW management prepare for this self-sufficient future with a further Government equity injection.

But the shift to complete commerciality didn't work.

Initially, KDW had hoped to ride out the financial storm and return to viability by reducing staff numbers, but it soon emerged that the Company's level of insolvency was greater than had been previously imagined. The result was a drastic rationalisation plan which the Board of the Company presented to Government in May 1988. It amounted, in effect, to the total closure of KDW: the London shop was to be immediately closed; the Company's retail and consultancy operations were to be wound down in an orderly fashion and its assets, principally properties, sold. The Kilkenny name, it was envisaged, would endure in the sale of the shops as going concerns but the entity known as Kilkenny Design Workshops would cease to exist.

Detail of Cornel Modem, Nathelie Newman and Oliver Hood, 1983 (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

Detail of Cornel Modem, Nathelie Newman and Oliver Hood, 1983 (Collection National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) NCAD, Dublin)

AFTERMATH:

PROTECTING THE PAST AND SECURING THE FUTURE

The potential demise of KDW was a source of public speculation before it was officially confirmed.

When news broke in early May 1988 that the Kilkenny shops were set for sale, it elicited appeals to Government to remove the cloud of uncertainty that now hung over it. None would be forthcoming and as soon as the decision on its closure was understood to be irreversible, the local political focus shifted from saving the Company to the safeguarding of its legacy. If Kilkenny was going to lose KDW, it could at least protect that which KDW had helped to create, most obviously the beautifully (and expensively) renovated properties of Butler House and the Castle yard.

The prospect of their sale, raised in the initial rationalisation plans of the Company, had already elicited a political backlash from local TDs and Councillors. At a heated meeting of Kilkenny Corporation, the defiant message delivered to both the KDW Board and to prospective buyers was unambiguous: Hands off Kilkenny Design Workshops, it's for the people of Kilkenny. Councillors, alongside cultural interests such as the Kilkenny Art Gallery Society and the Butler Society, were to the fore of a determined local campaign that ultimately succeeded in protecting the KDW complex from competitive sale. The campaign targeted, amongst others, the Taoiseach Charles Haughey who, it was claimed, personally intervened to defer the sale of the property. This was enough to ensure the site never made it to the open market. Instead, on foot of a proposal from Kilkenny County Council, ownership of the entirety of the KDW complex was sold at a lower than market rate to Kilkenny Civic Trust, a registered charity created by the Council for the purposes of its acquisition.

On the closure of KDW in the late 1980s, Butler House and the Castle stables were acquired by the KilkennyCivic Trust. (Image courtesy of Kilkenny Civic Trust)

On the closure of KDW in the late 1980s, Butler House and the Castle stables were acquired by the KilkennyCivic Trust. (Image courtesy of Kilkenny Civic Trust)

The decision to transfer to the Trust was widely welcomed. Maintaining the site in public ownership was, Councillor Margaret Tynan — Mayor of Kilkenny — justifiably trumpeted, “one of the most important decisions to be taken about Kilkenny in the last 40 years.” The Kilkenny People clearly concurred. But in praising the local efforts to save the site and the enlightenment of Government and senior civil servants in facilitating the transfer to a debt-free Civic Trust, the newspaper editorialised on the challenges and opportunities that lay ahead: ‘Now the real work must begin. The real benefit of having the premises under local control must not be lost. There is a great opportunity ahead but it needs the continuing efforts of all those who worked so hard to-date.’ The challenge set down was clear: however big a blow it was to lose KDW, the responsibility now lay with the Civic Trust and the business and political community in Kilkenny to build upon its achievements and secure its local legacy.

LEGACY

The decision to wind down KDW was an urgent, pragmatic response to two overlapping crises: the first, a crisis caused by the disastrous opening of the London shop and the resultant rapid deterioration in KDWs balance sheet; the second a crisis of Irelands public finances which narrowed the scope for Government intervention beyond fast fixes and damage limitation. But if KDW was a victim of a particular set of economic and political circumstances, it might equally be considered a victim of its own confidence and success. The expansion of its retail into London had been undertaken in the expectation that it would help drive the transition of KDW to full commerciality. Meanwhile, the changes to Irelands design culture that KDW helped to effect had done much to lessen reliance on the services and promotional lift the workshops had provided.

A small exhibition of KDW products and prototypes attracts 2,000 visitors across a two-week period inNovember 1965 (Irish Photo Archive)

A small exhibition of KDW products and prototypes attracts 2,000 visitors across a two-week period inNovember 1965 (Irish Photo Archive)

This reality fed into wider responses to the news of KDWs demise. For although nobody revelled in the closure of the workshops or the sale of the retail outlets, beyond the fretful local reaction in Kilkenny, the sense of loss was lessened by an appreciation that design now possessed a far greater profile in industry and beyond than at any point previously.

The Board of KDW acknowledged as much when, in presenting its own rationalisation plan, it reflected on its achievements in developing Irish design capabilities: across twenty-five years, it had helped raise consumer awareness of good design; afforded training opportunities to a generation of young designers; and assisted in developing a self sufficient and independent design industry. The truth of this was reflected in the diminished share of the design services market held at the end of its life in 1988. Where, fifteen years previously, KDW had provided almost all the design services to firms and organisations in Ireland, by then it delivered only about a quarter of those same services. As a senior Department of Taoiseach official observed in January 1988: there is now a case for a very reduced activity by KDW in this area if not complete withdrawal. In terms of design standards and education, the Ireland which KDW departed was unrecognisable from the one into which it had been born. It was both different and considerably better and there was a general consensus that KDW had been instrumental in ensuring this improvement. The place of Kilkenny in Irish design history is therefore assured. It has nevertheless been copper-fastened in the various retellings of the workshops story by those who experienced it first-hand, and by the academics and writers who have written of the uniqueness of this State-supported enterprise and its multifaceted legacy. Part of this legacy was the establishment of Kilkenny as a centre of arts, crafts and design excellence - the evidence for which is all around us today.

William Walsh and Jim King, pictured on either side of Taoiseach Jack Lynch and Minister George Colley, c. 1966 ('The Tom Brett Collection, Kilkenny County Council and Kilkenny Archives’)

William Walsh and Jim King, pictured on either side of Taoiseach Jack Lynch and Minister George Colley, c. 1966 ('The Tom Brett Collection, Kilkenny County Council and Kilkenny Archives’)