“A truly historic opportunity for a new beginning”

Thanks to the Good Friday Agreement, signed on 10 April 1998, an entire generation on the island of Ireland has grown up free from the shadow of violence.

The Agreement allowed us to reimagine what we think of ourselves and of each other. It transformed how the world saw our island and its potential.

The insecurity and violence of the Troubles gave way to a new confidence and hope for a better future. Northern Ireland has become a favoured location for international investment. Harnessing the potential of the all-island economy has created opportunities for families and communities across the island.

Together we have achieved things that previous generations thought impossible: from paramilitary decommissioning, to reformed policing, to an entire infrastructure for political engagement and cooperation East-West, North-South and within Northern Ireland.

For many, this is an ‘imperfect peace’. Much work remains for us to truly fulfil the vision and values of the Agreement that was signed in Belfast and to make sure that all communities and all traditions can fully reap the benefits of peace. As a co-guarantor of the Good Friday Agreement, the Government of Ireland remains profoundly committed to the ongoing journey of peace and reconciliation on and between these islands.

“The tragedies of the past”

In 1969, non-violent campaigners for civil rights were met with a hostile and repressive response from the authorities. The period also saw violent activity by paramilitary organisations representing minor elements within both communities. This was the beginning of the period known as the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

The Troubles cost over 3,500 lives, with many more injured and traumatised. Each of those lost left behind a grieving family, many of whom would spend decades searching for truth and justice. The lives and potential destroyed by acts of violence became a blight that remains a struggle to this day. Communities across Ireland and Britain were deeply impacted. A geography of trauma from Derry to Ballymurphy and Kingsmill, Dublin, Monaghan and Birmingham, Enniskillen and Omagh to London, is etched deeply in many hearts.

The Troubles entrenched divisions in Northern Ireland. Communities only streets apart observed strict segregation. Normal political life was made impossible, epitomised by the prorogation of Stormont in 1972. With the exception of a brief period in 1974, Northern Ireland was governed directly from London until the Good Friday Agreement made a new democratic dispensation possible.

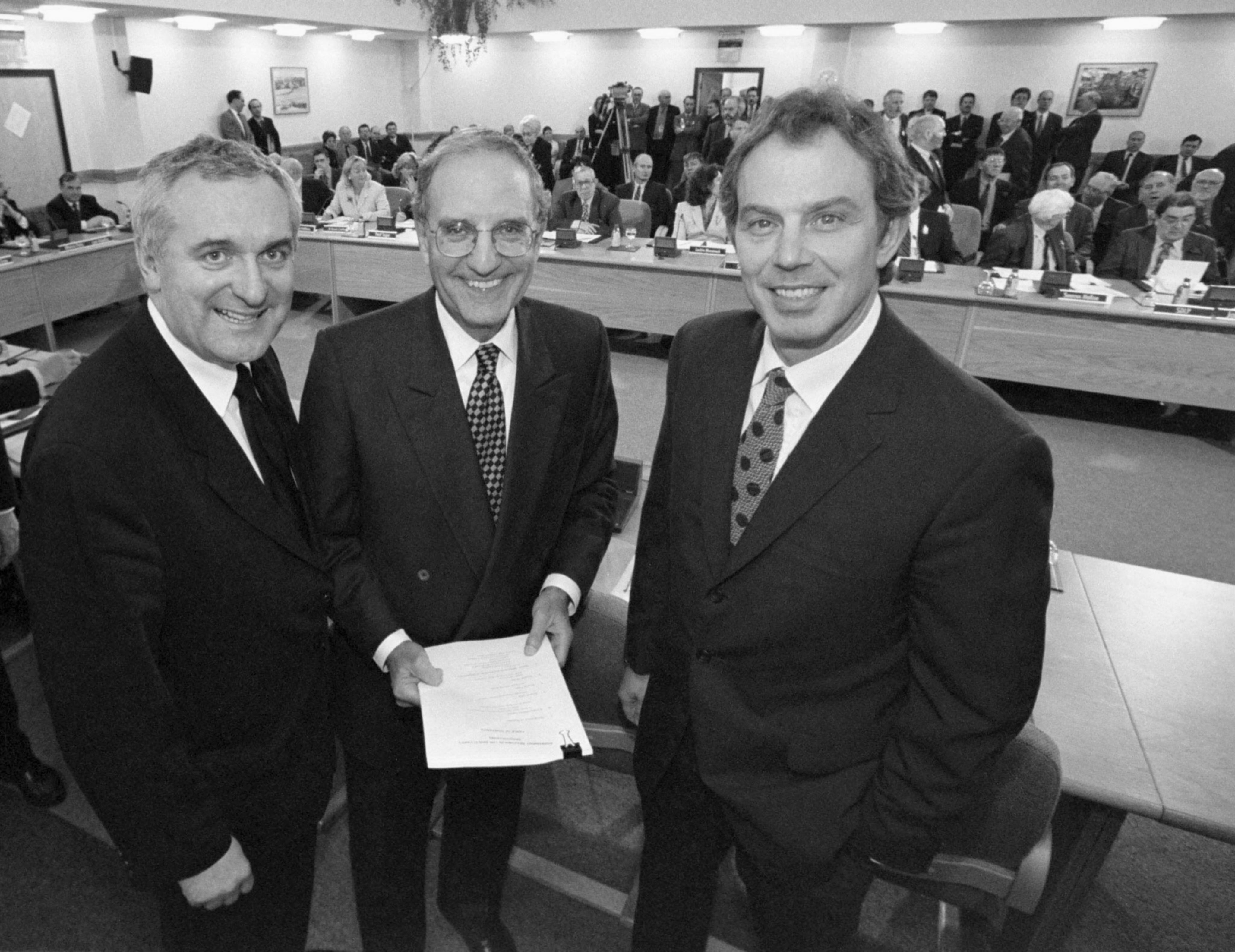

In the 1980s with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, the British and Irish Governments started to find structured ways to work together towards a negotiated, political solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland. Personal relationships from the level of Prime Minister and Taoiseach right down to officials working on day-to-day issues helped to create bonds of understanding and greater appreciation for the different perspectives on issues. This cooperation culminated in the Good Friday Agreement, which was agreed between the Northern Irish parties and the Irish and British Governments on 10 April 1998.

The two Governments’ roles and responsibilities as co-guarantors of the Agreement remains a defining feature of the bilateral relationship today.

“The tragedies of the past”

The Good Friday Agreement states that the best way in which to honour those who died or who were injured is to redouble our efforts “to the achievement of reconciliation, tolerance, and mutual trust, and to the protection and vindication of the human rights of all.”

The legacy of the past continues to deeply affect many families and communities across these islands. After the almost unimaginable trauma and loss they suffered during the Troubles, victims and their families were asked to make significant sacrifices that were pivotal to achieving peace, including around the release of prisoners who had perpetrated violent attacks. As with many post-conflict societies, Northern Ireland today continues to struggle with the legacy of violence, including through elevated levels of mental health issues and suicide.

Ballymurphy families and their supporters

Ballymurphy families and their supporters

Reconciliation remains a key goal of the Good Friday Agreement. This cannot be fully achieved without adequately addressing the legacy of the past, in a way that respects international human rights law and centres the needs of victims. Victims have often been frustrated by lack of progress in the attainment of truth, justice and accountability. Without an agreed way forward on addressing the legacy of the past, genuine and deep reconciliation will remain a challenge.

1985

Anglo-Irish Agreement

1993

Joint Declaration

(Downing Street Declaration)

1994

Paramilitary ceasefires

1996

IRA end their ceasefire

1997

IRA resume ceasefire

Independent International Commission on Decommissioning established

1998

Good Friday Agreement agreed in April

Referendums take place in May

1999

Devolution of powers to Northern Ireland

2001

PSNI established

2004

International Monitoring Commission established

2005

IRA announce end to armed campaign

2006

St Andrews Agreement

2010

Hillsborough Agreement

2014

Stormont House Agreement

2015

Fresh Start Agreement

2020

New Decade New Approach Agreement

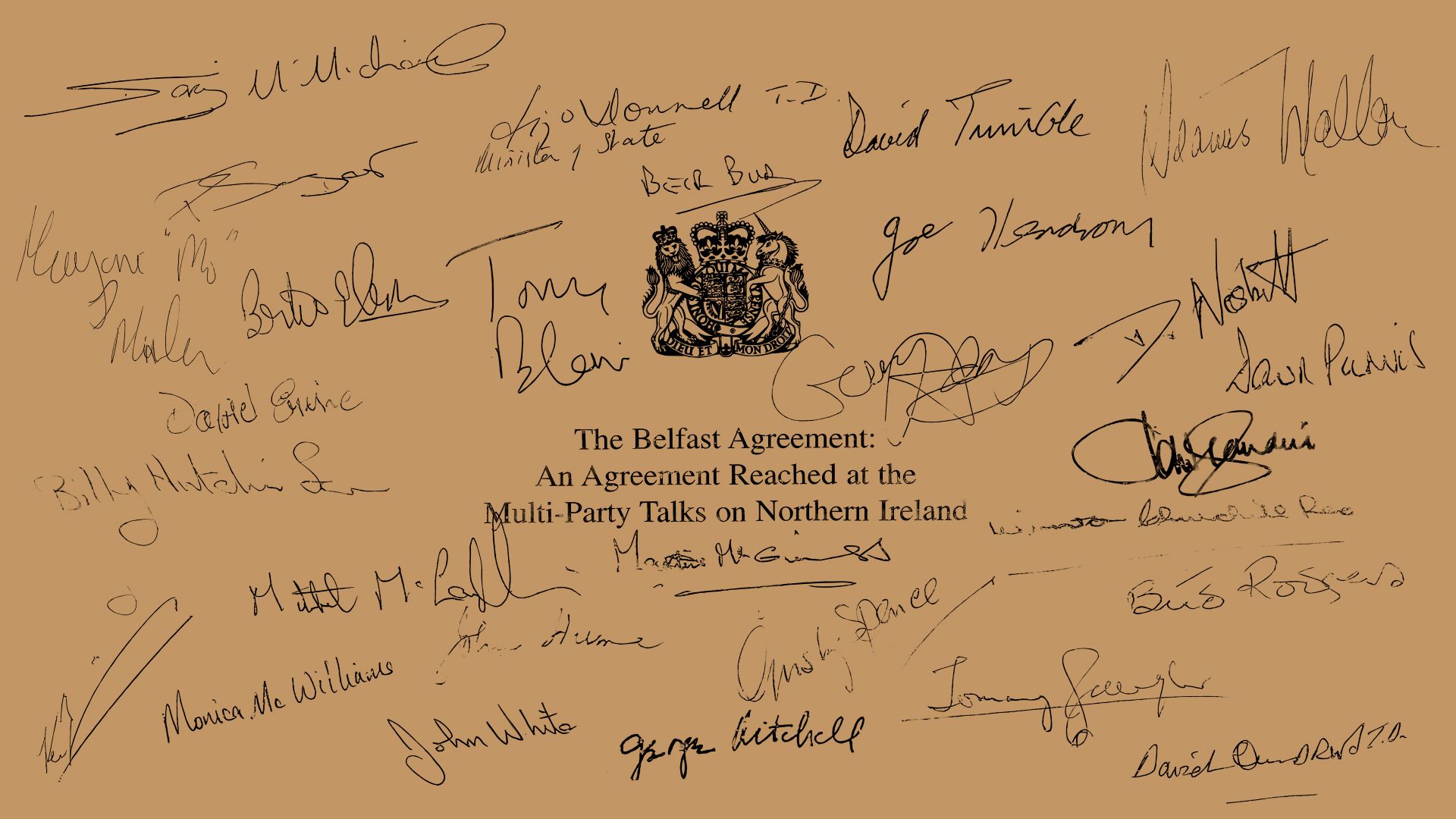

“We, the participants in the multi-party negotiations”

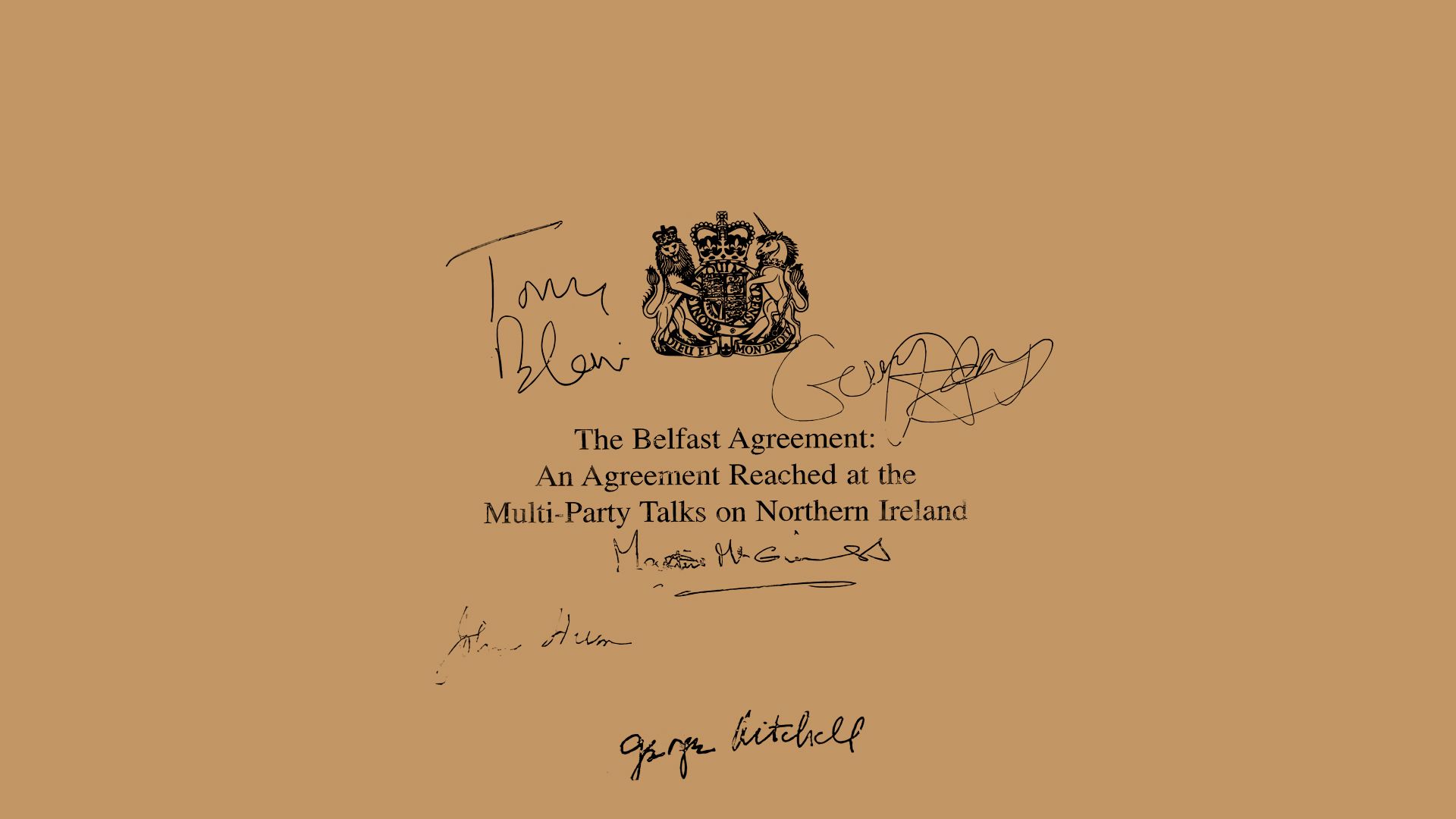

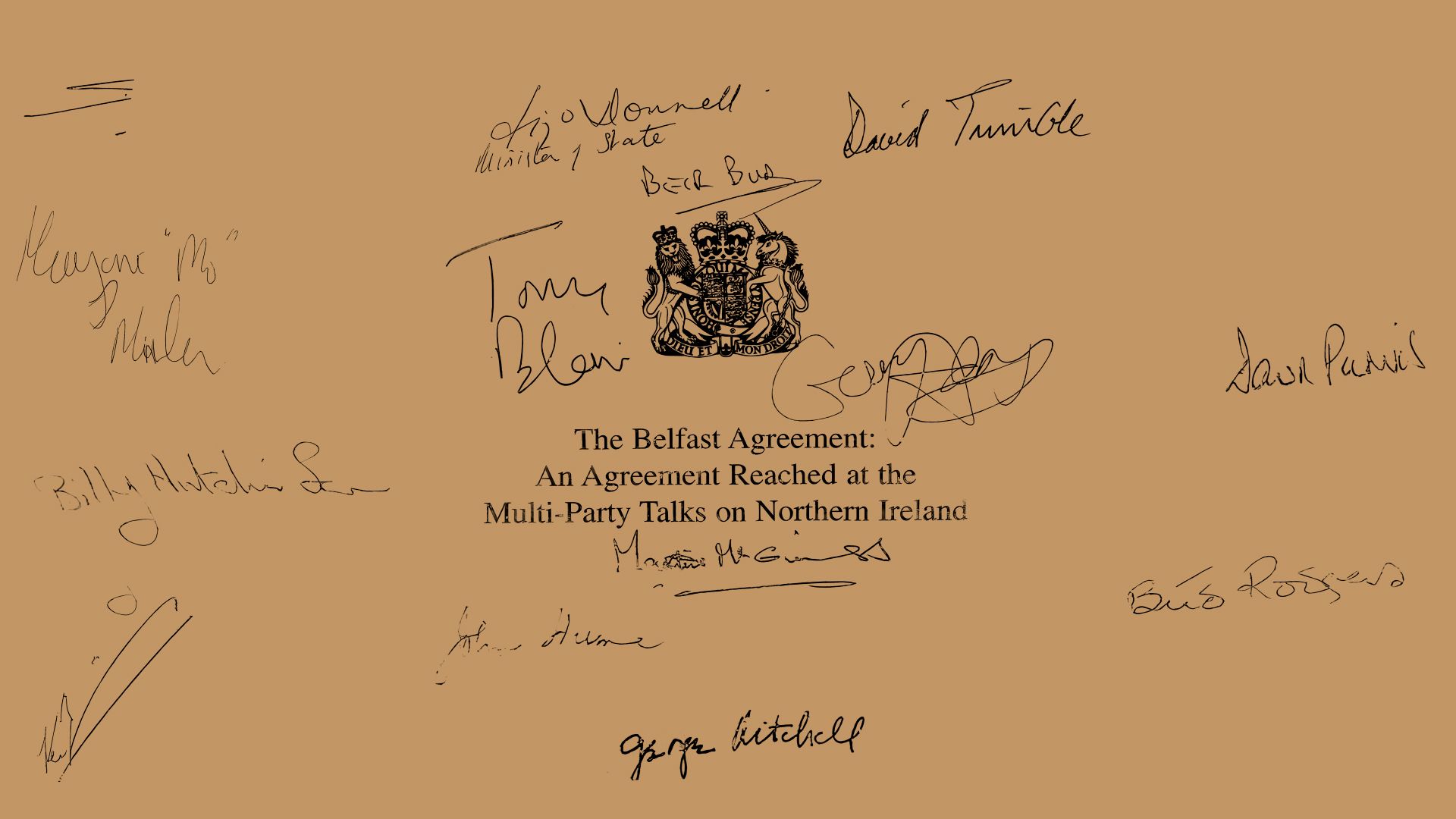

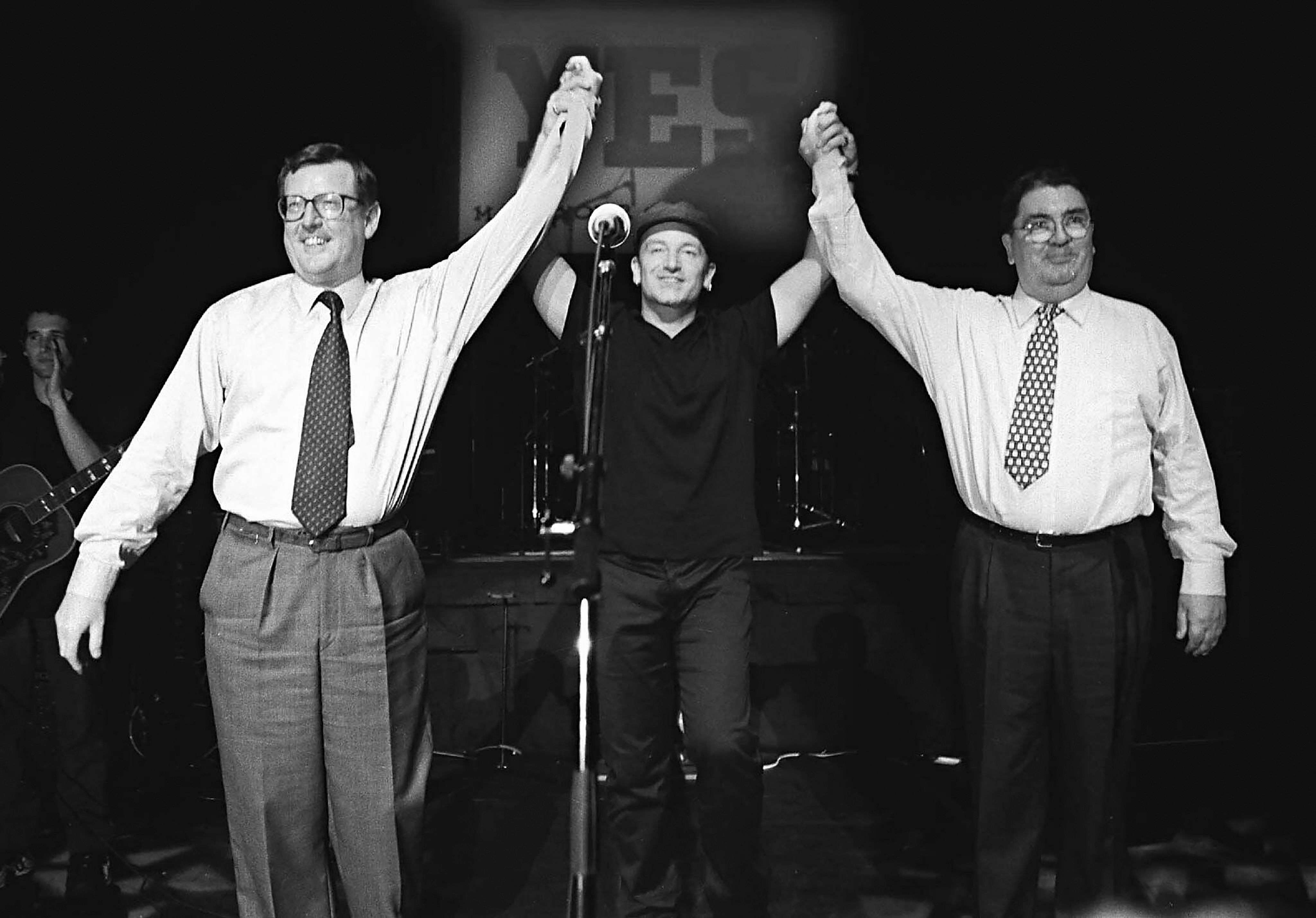

The Good Friday Agreement was achieved as a result of people from diverse political and civic backgrounds bravely coming together to work for peace. They faced down critics in their own parties and communities to make Northern Ireland a better place.

Activists from civil society fought hard to ensure that diverse voices had an input into the Good Friday Agreement. Some of the most pivotal actors of the peace process remain unacknowledged. Many women, in particular, played pivotal parts in their communities in building meaningful connections across divides, diverting young people away from violence, and demanding a better future.

Peace is the work of generations. What was achieved in 1998 did not happen overnight, but was made possible by years of ground-work put in by civic and political leaders from across Ireland and Britain. Each step taken, from the Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985), to the Downing Street Declaration (1993), to paramilitary ceasefires in the years leading to 1998, put us on a surer footing to peace. Each act of trust created new possibilities and new opportunities for leadership.

Today, civil society leadership from across the traditions and communities of this island remains at the heart of the process of peace and reconciliation. Supporting this work is a key priority for the Government of Ireland, through mechanisms such as the Reconciliation Fund, International Fund for Ireland, Shared Island Fund and EU PEACE monies.

“Our total and absolute commitment to exclusively democratic and peaceful means of resolving differences on political issues”

The Good Friday Agreement is a remarkable document that contains an inspired combination of practical mechanisms with visionary ideals.

At its heart are a number of fundamental principles, foremost of which is a commitment to “exclusively democratic and peaceful means” to resolve

political disputes.

The Agreement explicitly recognises that individuals and communities have different aspirations for the future of the island, all of which are legitimate, but affirms that these will only be pursued peacefully.

It recognises the complexity of peoples’ identities, acknowledging that the people of Northern Ireland can be “Irish, or British or both”.

Instead of pushing people into separate corners, the Agreement found new ways for us to come together in a mutually reinforcing ‘three-stranded approach’ that reflects the totality of relationships across our islands: North-South, East-West, and within Northern Ireland. This included new political mechanisms to help us better understand one another and deliver real improvements to people’s daily lives.

Central to these are the Assembly and power-sharing Executive established under Strand One; the North-South Ministerial Council established under Strand Two; and the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference and British-Irish Council established under Strand Three.

Partnership, equality and mutual respect are at the heart of the Good Friday Agreement, not least through the binding commitments given to “the protection and vindication of the human rights of all”.

The Agreement provided us with the tools we need to achieve a goal that all could agree on: lasting peace and true reconciliation. We have sometimes fallen short of this vision; but our commitment to see it realised remains.

International support

The support of the international community was essential to achieving negotiated peace in Northern Ireland. The names of the United States’ George Mitchell, South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa, Finland’s Martti Ahtisaari, and Canada’s John de Chastelain, are all inscribed in the annals of our island’s history as great peacemakers. They acted as neutral arbiters who were able to bring people to the table when nobody else could and were trusted to verify that all parties had lived up to their commitments.

The role of the US as a steadfast friend of peace spanned political generations on both sides of the aisle. Strong bipartisan support from both President Ronald Reagan and Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill was essential to the early years of the peace process. The impetus for peace created by the dedicated engagement of the Clinton administration was sustained by each of his successors, who demonstrated their ongoing commitment through political engagement, financial support and investment, and the appointment of a series of Special Envoys that continues today.

The support of the European Union to peace and reconciliation on the island of Ireland remains essential. The EU’s own genesis as a project to cement peace in Europe ensured an instinctive sympathy and support that endures. Ireland and the UK’s common EU membership and the practical framework for economic and political cooperation removed significant barriers. As we navigate the complexities caused by the UK’s decision to leave the EU, protecting the Good Friday Agreement remains the Government of Ireland’s absolute priority.

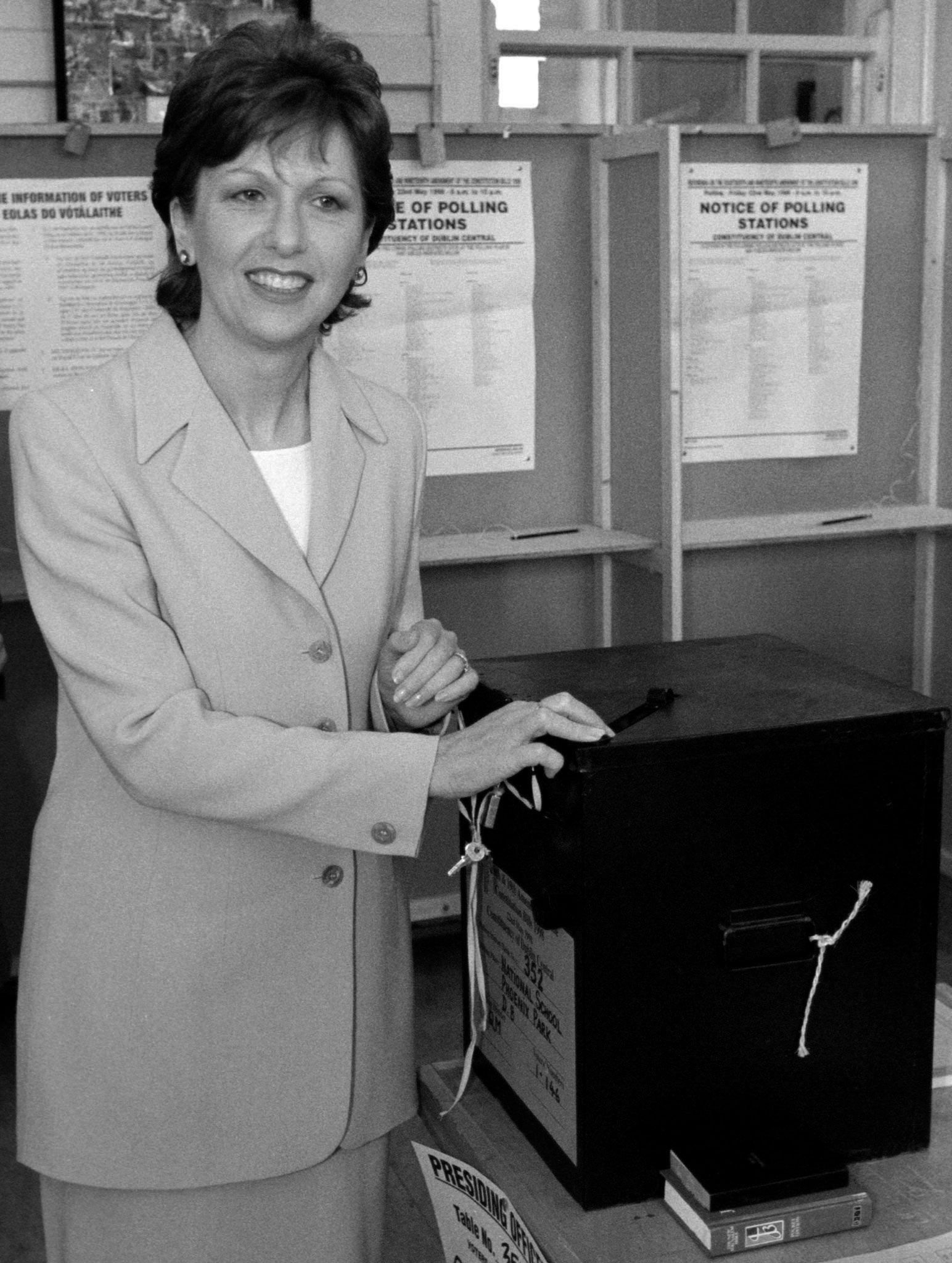

“We strongly commend this agreement to the people”

The people of Ireland, north and south, overwhelmingly endorsed the Good Friday Agreement in two referendums held on 22 May 1998. In Northern Ireland voters approved the Agreement and in Ireland voters approved both the Agreement and changes to Articles 2 and 3 of Bunreacht na hÉireann, the Irish Constitution (in line with the commitment made in the Agreement).

In Ireland 94% of people voted for the Agreement and in Northern Ireland 71% voted in favour. The overwhelming democratic endorsement of the Agreement guarantees its enduring legitimacy - the Agreement belongs to the people of this island in a unique way.

Each household on the island of Ireland received a copy of the Agreement. The merits of the Agreement, and the hard compromises that its acceptance entailed, were discussed and debated by families and friends at kitchen tables, in local pubs, and in community centres. Collectively, the majority of people north and south, irrespective of creed, tradition or background, agreed that we would build a peaceful future together."

“The achievement of a peaceful and just society”

The Government of Ireland remains utterly committed to seeing the Good Friday Agreement fulfilled in its entirety.

There is much work left to do. We are still a long way from the truly reconciled society promised in 1998. Important divisions remain both physically – in the ‘peace walls’ remaining in some communities – and psychologically, in the too-slow growth of truly shared experiences.

Moreover, the gains of the peace process have not been distributed equally, for too many, the absence of conflict has not been enough to feel the dividends of peace. Many communities still struggle deeply with the long-term consequences of the conflict, from acute social deprivation and mental health challenges to the ongoing influence of paramilitary organisations.

The power-sharing institutions of the

Good Friday Agreement played a pivotal role in bringing together people from across the political spectrum, to work together to make Northern Ireland a better place. However, the long periods that the people of Northern Ireland have spent without representation while their institutions have not been functioning shows us that there is more work to do to embed enduring political stability.

As we look to the future, the Good Friday Agreement remains the compass guiding us forward. Fulfilling its vision requires continued leadership from all stakeholders – North and South, East and West, as well as the support of our international friends and partners. We will never return to the dark days of the past. Working together, we can ensure that the next 25 years delivers a brighter future for us all.